Section One:

Patterns of Time-

The Seventeenth-Century

The Protestant Reformation changed England. It fundamentally changed the relationship that people had with religion. Protestantism encouraged a personal relationship with faith and individual reading of the scriptures. By the start of the seventeenth century, the Protestant Reformation had been established. The seventeenth century became a period of tension and conflict as Englishmen and women contended with one another over the meaning and course of English religious life. This led to chaos and contradiction in social and political life. Focusing on funeral sermons as a mechanism of public discourse provides a way to assess societal concerns about gender roles and expectations over the course of the century, giving this project scholarly significance.

Figure 1: "godly" Google Ngram

To gain a better understanding of some of the larger trends of the seventeenth century Google Ngram viewer was consulted. The visualization above uses Google Ngram to display the selected term in the British English corpus of books digitized by Google that were published in Great Britain between 1600-1700. While this is a broad and basic search, the search highlights a potentially significant data point: the use of the term 'godly' spikes in the mid-seventeenth century. This initial finding confirms a commonly understood historical development. The conflict over the extent of Reformation in England became a matter of great conflict with the Civil War coinciding with this spike in usage of the term. As will be seen in other visualizations, the mid-century saw a similar spike in funeral sermons.

During the middle of the seventeenth century, the Long Parliament dominated political life. Beginning in 1640, many long-standing tensions came to a head in English political life. There were those that supported the king, and those who opposed his policies. These divisions carried over into Parliament itself and became more apparent (Bucholz & Key, 245-250). Under this Parliament the country collapsed into Civil War and the king was executed. Pertinent to this study, the Long Parliament also abolished censorship during its period of power (Bucholz and Key, 264). This allowed for greater freedom in regards to what was printed and published and therefore could be, in part, why there are spikes in various graphs during the mid-seventeenth century.

As with most human rituals, the funeral sermon-especially those that went into print-served a variety of purposes beyond simple commemoration of the dead. Ritual and traditions saw as much change as that taking place in society and politics. Funeral sermons, of course, commemorated the dead. However, such commemoration came under scrutiny from those who saw elaborate death rituals and commemoration as too much akin to "popish" or Catholic ritual. Praising the dead too much could get you into trouble with the more fervent sorts of Protestants. Funeral sermons offered a way for the pastor to direct the listener and the reader in how to live a godly life. In addition, sermons could serve as prescriptive literature to police the boundaries of social and gender expectations. Certainly, the funeral sermon acted as a means for shaping and cementing the reputation and memory of the dead. As Peter Marshall states, "The funeral sermon itself, however, was the most conspicuous instrument of post-mortem reputation as the sixteenth century drew to a close…Their official rationale was the edification of the living, not the exaltation of the dead" (Marshall, 274).

Because social order was so important to early modern England, funeral sermons became an avenue for social control. Lucinda Becker, in Death and the Early Modern Englishwoman, argues, "these publications were not produced simply to ameliorate the fear of death; they were also used to exploit the natural anxiety over death and dying, at times employing 'an element of shock tactics in the deliberate evocation of the horrors of death' in order to ensure religious observance and social compliance" (Becker, 11). If preachers and those involved in producing these sermons could scare people into compliance with social standards, then that would be what they would do. Rather than have people begin to create their own ideas about how to live a good and faithful live, they should be told how to do it in a way that made them feel as though they still had time to amend their mistakes and learn from those that came before them. But it also became about balancing that fear along with providing some comforts to the living who just lost a loved one. In Thomas Taylor's sermon, The Pilgrim's Profession, he tries to assuage the feeling of fear people had regarding death. In the facsimile and reprint, done by Retha Warnicke and Anne Doebler, Taylor is quoted as stating, "The third encumbrance is the feare of death which presseth us all our life; and the Christian must lighten himself of this burden by looking beyond it to his owne home; by longing after the living God, whome none can see in the body and live; by considering that the nearer he is to death, he is so much neerer home" (Taylor, 83-84). This shows that while the fear of death and dying was present, it was not always highlighted in the sermons. The language, tone, and content of the sermons would also reflect the particular Protestant theology of the preacher, the deceased, and the surviving family.

Figure 2: Seventeenth century funeral sermons by decade (both women and men)

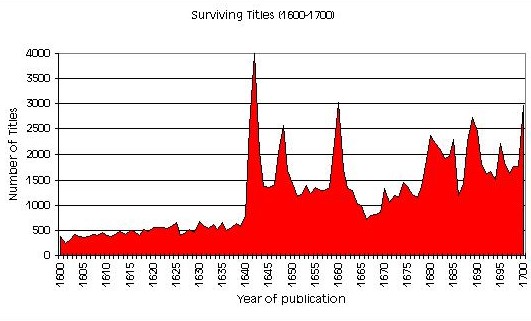

The chart above shows the spike in the middle of the century at a time of turbulent political and social change. It also shows that that rise is overshadowed by the increase that occurs in the last decade of the century. These numbers are a grouping of sermons regarding men and women and can be seen as a small sampling of what some of the larger trends of the century may have been. When set against the data obtained from the English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC) it is clear that the jump in overall number of funeral sermons coincides with a similar spike around 1642 of all publications. As with the funeral sermons, the ESTC data reflects only the data for surviving publications.

Figure 3: ESTC graph of surviving titles (1600-1700) [Graph found here]

Figure 4: Cirrus visualization of book catalogs

In the course of this research, in addition to the funeral sermons themselves, found among the sermons were published personal library catalogs from the collections of early modern book owners. During my initial search through Early English Books Online, I came across a handful of these catalogs that suggest an interesting avenue for future research. This project deals with the variety of purposes of funeral sermons when both spoken and printed. However, these library catalogs indicate that at least some people collected funeral sermons. What people decide to keep in their libraries tend to be reflective of the culture of that time period. Because of this, it seemed relevant to run the seven documents through Voyant to see what terms came up the most in the Cirrus tool. Searching through I looked for terms that would hint at religious and hierarchical trends that are present in the funeral sermons. Rather than necessarily finding any direct evidence in those terms, Cirrus helped to show the important years for these collections as well as what subjects were most important to men at this time. It is clear that sermons, both funeral and those on other topics such as history or religious events dominated the collections. It might also be worth noting that many of the dates that show up in Cirrus are after the middle of the century mark, which seems to be where publications, of varying natures, spike. This may be an indication of the trend of publishing sermons and the subsequent collecting of them gained traction after 1640. To explore Cirrus yourself, hover your mouse over the different words to find out the number of times they were used in the corpus. Also in the lower left portion of the visualization you can search for particular terms and adjust the scale of terms for new perspectives.

Another potential area of future research would be to delve more deeply into an examination of those printers who printed the sermons. The sermons would be lost to history and memory if a printer had not produced a printed version of the sermons. Who these printers were and how it might relate to larger issues of printer networks and the interplay of politics and religion would prove a useful endeavor. While looking through my corpus of sermons, I have come across various names of printers (some of the sermons have them listed, others do not) Using the London Book Trades Wiki and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography I did some very basic preliminary research into who these printers were. While there is not much information on most of the printers, extended research could usefully trace connections between printers, publishers, preachers, and the persons for whom the sermon was written. The information could benefit from resources such as Six Degrees of Francis Bacon.

Finally, below is another visualization using Google's Ngram Viewer. Rather than search a broad term like 'godly' again, it is useful to search terms that were particular to the Protestant Reformation as an ideology.

Figure 5: Protestant terms Google Ngram

The visualization above processes the terms: predestination and freewill, both terms that would suggest a "hotter" sort of Protestant mindset, such as that of Puritans. The jump in the use of these terms may reflect the heated debates over the prayer book and the further reformation of the Anglican Church in the years before the eruption of the Civil War. James I in the 1620s seemed to falter in his ability to manage the various religious factions and Charles I did not have his father's ability at all (Bucholz & Key). Based on the sheer number of publications, many of these tensions between religious factions broke out into the open and into print. Tracking word usage across time allows scholars the ability to trace public discourse and attitudes on a variety of topics.

While everyone in England may have lived through the Protestant Reformation, men and women experienced it very differently. These differences will be discussed in the next section.