This subject of this project originates, in part, from the research I have done as part of my masters thesis at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana. In my thesis, I examine the impact of processes of national identity formation on United States Indian policies during and after the American Revolution and the role of the failures of those policies in shaping subsequent policies and historical memories.

This belief was, I argue, in part the product of the failures of US Indian policies during the war. These policies were, I think, dramatically shaped by processes of national identity formation that began during the early years of the Revolution.

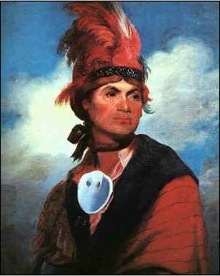

Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea)

Click to view a rough draft of my masters thesis.

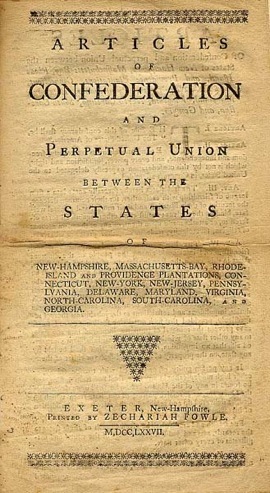

This idea in large part formed the foundation for much of US Indian policy during the early years of the war. It was first seen in the original draft of the Articles of Confederation written by Benjamin Franklin in 1775, which called for American officials to “reside among [the Indians] in proper Districts” in order to “take care to prevent Injustice,” and “relieve their personal Wants and Distresses.” It was elaborated upon by Congressional decrees issued a few months later, which instructed the commissioners Northern, Middle, and Southern Indian Departments to secure alliances with the Indian nations in their respective regions. According to Congressional leaders, this could best be accomplished through the “propagation of the gospel, and the cultivation of the civil arts” in Indian communities.

Click to view Franklin’s proposed Articles of Confederation.

This was all done in preparation for those Indians’ eventual assimilation into American society. Some Indians, like the Delaware and Oneida, embraced these efforts as an opportunity to preserve as much of their culture and independence as they thought possible. According to historian David Rich Lewis in his book Neither Wolf nor Dog, such efforts represent aspects of processes of cultural reproduction. As Lewis notes, nineteenth-century Indians of the American Southwest only accepted as many American cultural practices as were necessary to help them maintain a modicum of independence, and only those cultural practices that might help to facilitate their own. The actions of US-allied Indians during the Revolution were similarly motivated.

Of course, Congressional leaders were unaware of these motivations. Instead, they were so hopeful of the potential success of their efforts with such Indians that they explicitly planned for their specific assimilation into American society. These plans culminated in the Treaty of Fort Pitt in 1778, the sixth and final article of which declared that all tribes like the Delaware “who ha[d] been friends to the interest of the United States” could “join the . . . confederation” and “form a state” that would “have a representation in Congress.”

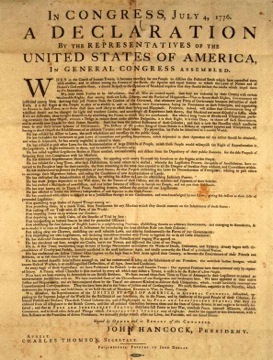

British-allied Indians, on the other hand, were declared savages by Congressional leaders. The most famous example of this can be found in the Declaration of Independence written by Thomas Jefferson, which blamed the king for endeavoring to bring on the “inhabitants of [the American] frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” This sentiment was echoed throughout 1776 and the later years of the war in Congressional missives, which bemoaned what American leaders called a series of cruel massacres against the “peaceable inhabitants” of the frontier by “tribes of Indian savages.”

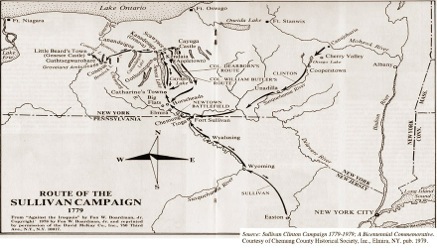

This belief was carried into execution in the Congressionally-ordered expedition against the British-allied Seneca Indians (who had been particularly effective in raids along the New York frontier). The expedition was assigned to the command of Generals John Sullivan (a veteran of the Long Island campaign) and James Clinton (who played a key role in the defense against General John Burgoyne’s invasion of New York). Over the course of the campaign, the Sullivan Expedition left a 150-mile path of destruction through Seneca lands. It destroyed over forty Seneca villages and left over five thousand Iroquois refugees without food or shelter.

Click to view the Declaration of Independence.

In the wake of what could be considered the first example of a governmentally sponsored campaign of total war in US history, Congressional leaders ordered the Seneca to vacate much of their land and move westward. After the US emerged victorious from the war, such demands became increasingly common in treaty councils held between Congressional agents and Indian leaders. Because the large majority of Indians had allied themselves with the British, American leaders believed that their lands were forfeit to the United States as the property of what Congress saw as defeated, conquered nations.

This idea was soon expanded to encompass even US-allied Indians, whom Congressional leaders considered insufficiently eager to embrace civilization and assimilation into American society. In 1785 at the Treaties of Fort McIntosh, Galphinton, Dumplin Creek, and Hopewell and in 1786 at the Treaties of Fort Finney, Chota, and Shoulderbone, Indian groups friendly and hostile alike were forced by American representatives to cede substantial portions of their own land and move farther and farther westward away from the boundaries of the United States.

With the establishment of the new federal government under the recently ratified US Constitution, an attempt was made by a number of prominent American officials (particularly Secretary of War Henry Knox) to return to policies geared toward the ‘civilization’ and assimilation of Indians into American society. The large majority of American leaders, however, largely ignored such efforts and continued to work to secure the forced removal of the entire Indian population east of the Mississippi River westward away from the new American nation.

Map of Sullivan Expedition’s trail through western New York.

Opponents to Indian removal predicated their arguments against the Act, in part, upon that fact. Those who opposed the Indian Removal Act of 1830 believed that, as ‘civilized’ Indians, the Cherokee were worthy of inclusion in the American nation. This belief is, I argue, an inheritance from the American Revolution.

Supporters of the Act, on the other hand, were still nursing old wounds from the war. Some of the most impassioned defenses of the Act recalled Cherokee attacks along the revolutionary frontier in tones of deep-seated bitterness in order to argue that the Cherokees had demonstrated their eternal ‘savagery’ in that war and were thus unworthy of protection from the American government.

The project featured on this website is an attempt to at least partially confirm this argument by finding connections between memories of Indian violence and the Indian Removal Act of 1830.