Censorship Topics

The close reading of the six months of bulletins from 1915-1916 provided a set of major themes to analyze within the larger corpus: violence, sexual, crime, harming society, drinking, gambling, and smoking. However when put into the context of the larger corpus, these themes did not always remain as prevalent as they were in the close reading of the select dates. What follows is an analysis of the entire corpus, identifying the major topics of the Board's censorship over a forty period and noting the ways in which they changed. Note that many of the embedded tools below are live so that you can interact with them. You are encouraged to use these tools to search through the corpus to answer any specific questions you might have, as well as to further test the conclusions presented in this study.

A Note on Dates

The bulletin dates of 1924, 1925, 1929, 1933, 1934, 1940, 1944, 1947, 1952, 1953, and 1954 were carefully selected for historical context and to track change over time. The years 1924 and 1925 are the first years (outside of the six months of 1915-1916) of archived bulletins available. These two years are situated at the height of the silent film era and come just a few years after the formation of MPPDA (the Hollywood self-censorship effort led by Will Hays). The year 1929 marks the significant transition from the silent era to "talkies" or sound films. The years 1933 and 1934 come in the middle of the great depression, but more importantly mark the formation of the Production Code Administration (an arm of the MPPDA) and the Catholic Legion of Decency. The years 1940 and 1944 provide a look at the Board's censorship during WWII, with 1940 being prior to U.S. involvement and 1944 nearing the end of the war. The final significant date is 1947 when Howard Hughes went to court over the censorship of The Outlaw, for this is the first court case since 1915 to make an argument against censorship on the grounds that films should be protected as free speech. The Outlaw is one of the Case Studies examined in a separate section of this analysis of the Ohio Censorship Board. The years of 1952-1954 are the final years of the Ohio Censorship Board. The 1952 Burstyn v. Wilson Supreme Court Case overturned the 1915 Mutual v. Ohio decision (which had declared that films were not covered under the First Amendment), Ohio censorship was still carried out but it was extremely limited. And, as examined in the history of the Board in the Overview section, the 1955 R.K.O. Radio Pictures v. Board of Education resulted in the end of Ohio's film censorship. This historical context was gathered heavily from film scholar Laura Wittern-Keller's informative timeline of film censorship in the United States, available here.Summary

Figure 14: Summary

To start off, the Summary tool provides some observations on the entire corpus. First is the document length. The years 1934 and 1933 are the longest because sound had been increasingly added to films since 1929. It was common for the Ohio censors to list entire pages of dialogue that they wanted eliminated from the films. In terms of shortest length, the later years of the 1950s had significantly less eliminations requested due to series of losing court cases and changing of public opinion. Some of the distinctive words listed point to the changing in type of censorship, where 1915 has "sub" and "title" for sub-title, while 1929 has "silent," "subtitlo" (subtitle), and "eliminate" because it was a transition year from silent to sound films. The censors would note this at the top of the film. The term "eliminate" is worth noting because prior to sound the censors would order something cut from a film, but after sound was introduced they ordered it eliminated (as seen in the trend below). By 1933 and 1934 the terms "eliminate," "dialog," and "remark" are becoming commonly used, as well as the character names that were included in the dialog elimination orders.

Figure 15: Trends: Eliminate/Cut

Major Topics

To determine these major topics the corpus was searched using both the terms identified in the close reading of 1915-1916 and terms that were noticed during the process of OCRing the documents. There were several terms that stood out distinctly from the rest in the topics of sexuality and violence, occurring over 200 times in the corpus. This high number of search hits shows that sexuality and violence were by far the most censored topics, but the themes of alcohol and crime should also be considered as significant. While terms regarding alcohol and crime did not come up as much, the topics themselves were highly influential to process of censorship. Alcohol and crime, as well as the minor emphasis on censoring matters of religion and race, will be analyzed in the Specific Examples section. One thing to note is that the categories of smoking and gambling were significant in the close reading of the 1915-1916 bulletins, but were not common throughout the rest of the corpus. It is unclear why this is a case, but it is probable that censorship became more broad as films became longer and more complex.

Trends - Over 200 Eliminations

Figure 16: Trends: Over 200 Eliminations

The image above is a trends tool tracking the appearance of specific eliminations that occurred over 200 times in the corpus. The asterisk next to the word indicates that variations were included - such as dance, dancing, dances. The terms are: Danc* which appeared 599 times, Kiss* 521, Nud* 213, Hit* 204, and Throw* 200. However it is important to note that this is a relative frequency and not a raw data. To change the view click on the button in the upper right corner next to the question mark and select "raw." This does not change the information but presents the data in a more viewer-friendly way. These major topics are a combination of actions and subtitles/dialogue, but one of the first things you might notice is that the numbers are far less than the tallies in the close reading. That is because, much like the censors in some of their summary documents mentioned below, the counting of categories is not the same as the searching for individual terms. For example, the tally for murder for the six months of bulletins of 1915-1916 is 126, while a search for the term mur* in Voyant for the entire corpus is only 137 results. Just like the censors, during the close reading if a line of elimination read "man beats man to death," I would mark that as a murder. But since the word is not stated is does not appear as part of the Voyant search. This is why it is important to have the research be a synthesis of close reading and distant text analysis. The close reading has provided the foundation and now the large text analysis of the entire corpus will enable us to recognize significant trends and themes of censorship.

For this analysis of the Board we are focusing on actions, since those are searchable within the corpus using Voyant. While in some of their internal documents the Board may have found it useful to organize their data using the terms: "indecent, inhuman, tending to incite to crime, immoral or tending to corrupt morals, sacrilegious, and obscene"; this research will focus on the actual eliminations (Statement of Films Censored, Dec 31, 1928, Rejected and General Correspondence). The vagueness of those categories and the overall state censorship statue are one of the reasons that the Supreme Court ruled against the Board in the 1950s, and they will not be utilized for this research (Wittern-Kellar, "History of Film Censorship"). Even the eliminations breakdown sheet upon which that list was written states, "in some cases eliminations were made on more than one ground" (Statement of Films Censored, Dec 31, 1928, Rejected and General Correspondence). Had this research been based around those categories it would be impossible to determine the actual content being censored, since something such as a woman undressing in front of a minister could be considered indecent, immoral, sacrilegious, and/or obscene. Focusing on actual eliminations and grouping them under topics, such as sexuality and violence, is a more effective method.

For the censorship boards in Ohio and other places, sexuality encompassed kissing and other methods of seduction (Wittern-Kellar 48). Dancing was by far the most significant thing censored in this corpus, far surpassing anything related to violence. Dancing was actually listed on the MPPDA's Production Code of 1930, "Dances suggesting or representing sexual actions of indecent passion are forbidden. Dancing which emphasize indecent movements are to be regarded as obscene" (MPPDA Production Code, 1930, Legal). Unlike the close reading which pointed to violence being the most important topic, sexuality (the combination of dancing, kissing, nudity and many other terms) is the most common theme censored by the Ohio Board, particularly in the latter years of censorship. When we trace the trends of just the terms kiss* and fight* (using relative frequency still) this inverse relationship is clear to see.

Figure 17: Trends: Kiss/Fight

The decrease in the censorship of violence during and after the 1940s could be attributed to the historical context. During WWII the film industry was considered an essential war industry and utilized heavily by the Office of War Industry. The industry produced war films, documentaries, and newsreels about the war, theaters sold war bonds, and stars entertained troops. One of the significant reasons for the major studios going along with the OWI is that by being declared an essential war industry they were given exclusive access to raw film stock. The smaller, independent studios who did not get this access were unable to sustain their business, and the number of independent and foreign films declined over 50 percent from 1939 to 1944, going from producing half of all films in 1939 to less than a fourth in 1944 (May The Big Tomorrow, 146). However while the major studios were able to create a monopoly, they had to contend with censorship from the OWI. The OWI censored films for content that was considered unpatriotic and counter to the war effort, and anyone who was not on board ran the risk of being investigated by the FBI, such as Orson Welles after the production of Citizen Kane (May The Big Tomorrow, 144-146). While there is a spike of the term "hit*" in 1940, it is not specifically related to war films. Below, a search for the term "sold*" and the trends of raw occurences reveals that war films were most likely not a major subject of censorship. Additionally it is worth noting that the term "sold*" only appears a total of 45 times, so the high numbers on the chart are not indicative of a major topic of censorship.

Figure 18: Trends-Raw: Soldier

The flood of violent footage in the theaters, the surge of war-time patriotism, and the increased involvement of major government entities all seem to contribute to the lack of censorship of violence by the Ohio Board in the 1940s. As Wittern-Keller notes, "The censors and the dissident distributors took a break during the patriotic fervor of the war years" (Wittern-Keller 88).

Gender

In addition to the major categories, the close reading of 1915-1916 bulletins also indicated a connection between gender and the types of censorship. Tracking the trends of the gendered terms (man, woman, girl, boy) shows that the terms appear with similar frequency

Relative Frequency

Figure 19: Trends-Rel: Gender

Raw Frequency

Figure 20: Trends-Raw: Gender

Examining these two trends reveals that neither gender was favored in the censorship. But the raw frequency shows that the gender terms of "man" and "girl" were used far more often. Searching these terms with other tools, such as the Collocates and Contexts tools, allows us to understand the correlations between those terms and some topics of censorship. Using the tool to search for the term "man" does not produce significant results beyond showing that the male figure was often censored for their actions toward other characters in the film (men and women, boy and girls). The girl, on the other hand, was often censored as an individual.

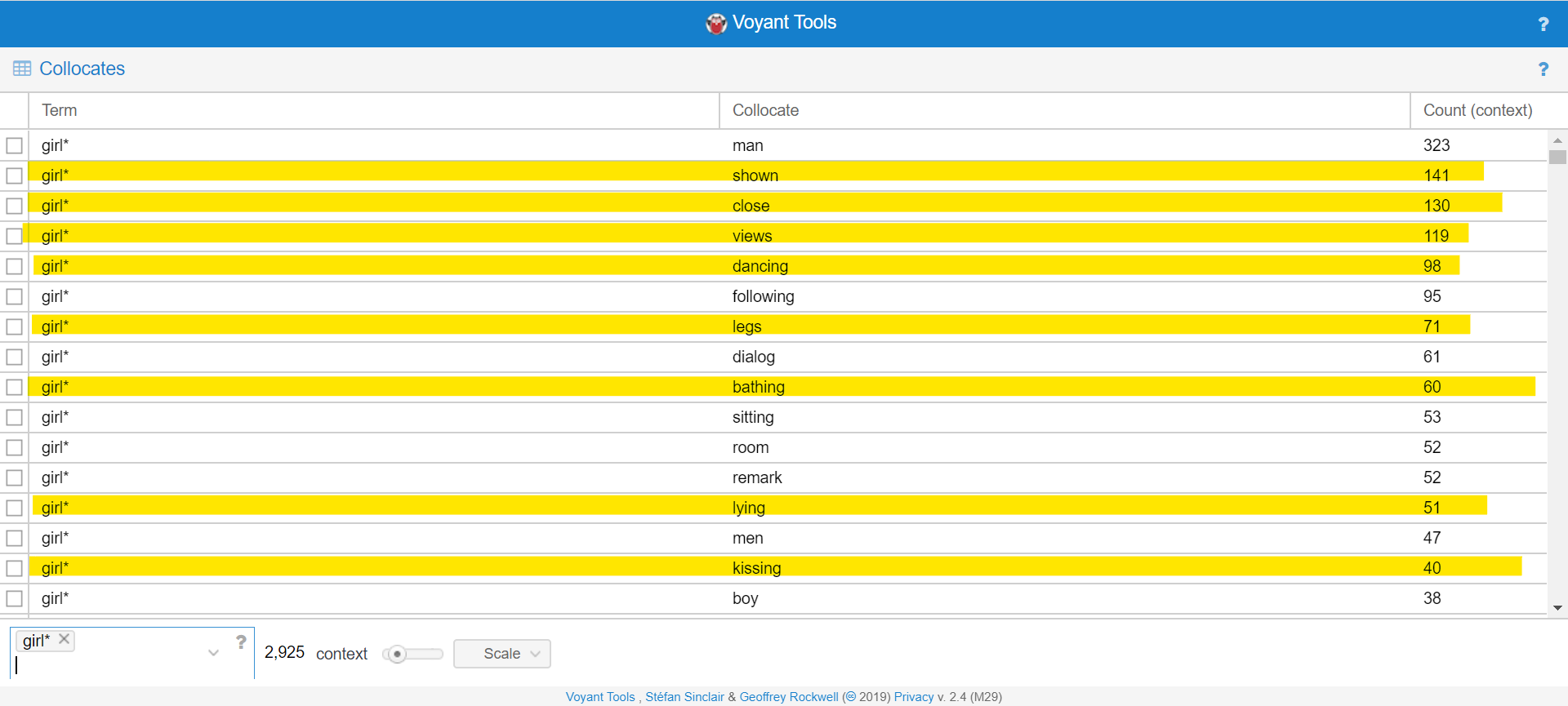

Girl

Figure 21: Collocates: Girl

Figure 22: Collocates: Girl - Sexual Content

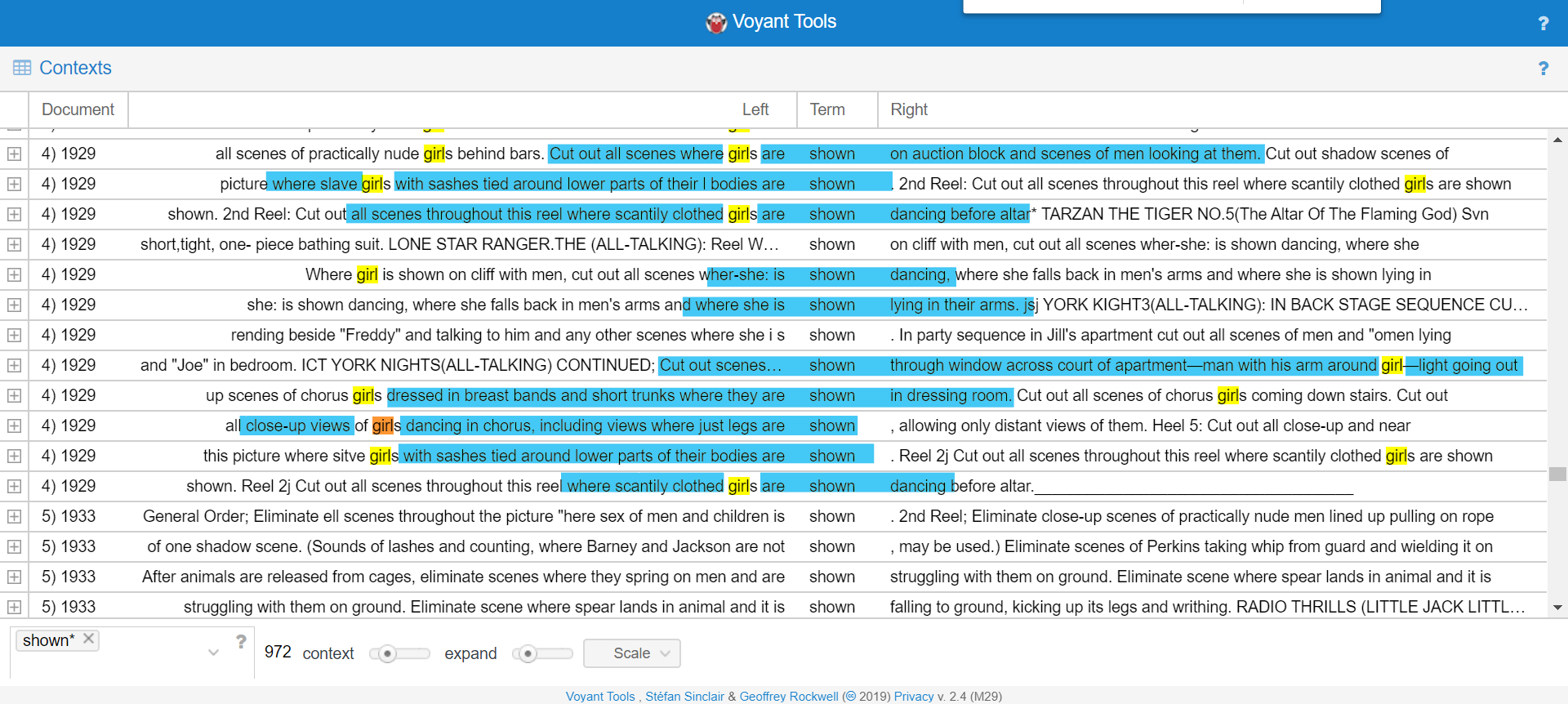

The collocates tool shows terms in relation to each other. The first one shown above is embedded so that tool is navigable. The second is an image that has been highlighted to show the major connections between "girl" and a sexual term, which is a majority of the collocates. At first it may not seem like the term "shown" is sexual, since it is used in diverse ways throughout the bulletins. But a look at the term "shown" in the Contexts tool shows that when the term is used next to "girl" it is often for a sexual purpose (remembering that for the censors sexual means anything related to seduction, kissing, and nudity).

Figure 23: Contexts: Gender

It is not a complete surprise that there is a strong connection between the term "girl" and the topic of sexual censorship. What is worth noting is that many of the terms on the collocates and the examples in the contexts are of nudity, dancing, and seduction, not primarily sexual acts. Especially in the 1920s during the rise of the Flapper image, characterized by her dancing, mass-marketed dress, and sex-appeal. As one historian of the images of women writes, "By the 1920s, public displays of sexuality were far from shocking; they were, in fact, expected of middle-class youth. And in films of the decade, the flapper behaved outrageously but only hinted at promiscuity," (Kitch 131). Restrictions upon sex and sexual freedom are traditional pillars of the Progressive reformers' agenda, upon which film censorship is based. The notion that society needs to be safeguarded from vice and immorality, rather than individuals choosing to guard themselves, is a pivotal idea in the argument for film censorship. But the film industry was developing simultaneously with the time it became "Sex O'Clock" in America, fueled by the popularization of the theories of Sigmund Freud and the rise of feminism (McGerr 261). It is thus no surprise that the Ohio Board of Film Censorship was not on board with the new understanding of sexuality that was developing in the early twentieth century.

Conclusion

By taking the findings of the Close Reading of the 1915-1916 bulletins and applying them to the whole corpus of bulletins the major topics of film censorship of the Ohio Board is determined. By a landslide sexuality, both explicit sexual scenes and more suggestive scenes such as dancing, was the main topic of censorship. Distantly behind sexuality was violence, alcohol, religion, and race. The latter three will be examined in the Specific Examples section, going into detail on the instances of those censorship throughout the corpus. Additionally it was confirmed that, just like in the close reading, there is a connection between gender and the content being censored - with girls being censored individually for sexuality while men were censored largely for their actions towards other individuals in the film.