Specific Examples

The major topics of censorship for the Ohio Board of Film Censorship are sexuality, violence, alcohol, and crime. A list of content topics was first identified in the close reading, refined and analyzed in a study on the entire corpus of bulletins, and now will be examined in close detail. Since the censorship topics page previously focused upon the major topics of sexuality and violence, this page will look at some specific examples of the more abstract topics. Alcohol is a major topic within its historical context of the prohibition. Crime, as previously discussed, was a catch-all category for that was stated to be the Board's major topic of censorship. In the close reading of 1915-1916, some of the eliminations were grouped under a "harming society" banner, but for the distant reading those topics of bombs, riots, mobs, etc. will be included in crime. While that category was useful for an early understanding of the types of censorship, at this point in the analysis those topics are better understood under the category of crime. Not only are they listed that way in the production code (1930), but it is also listed that way in the Board's eliminations breakdown document of 1928 - discussed in the previous section.

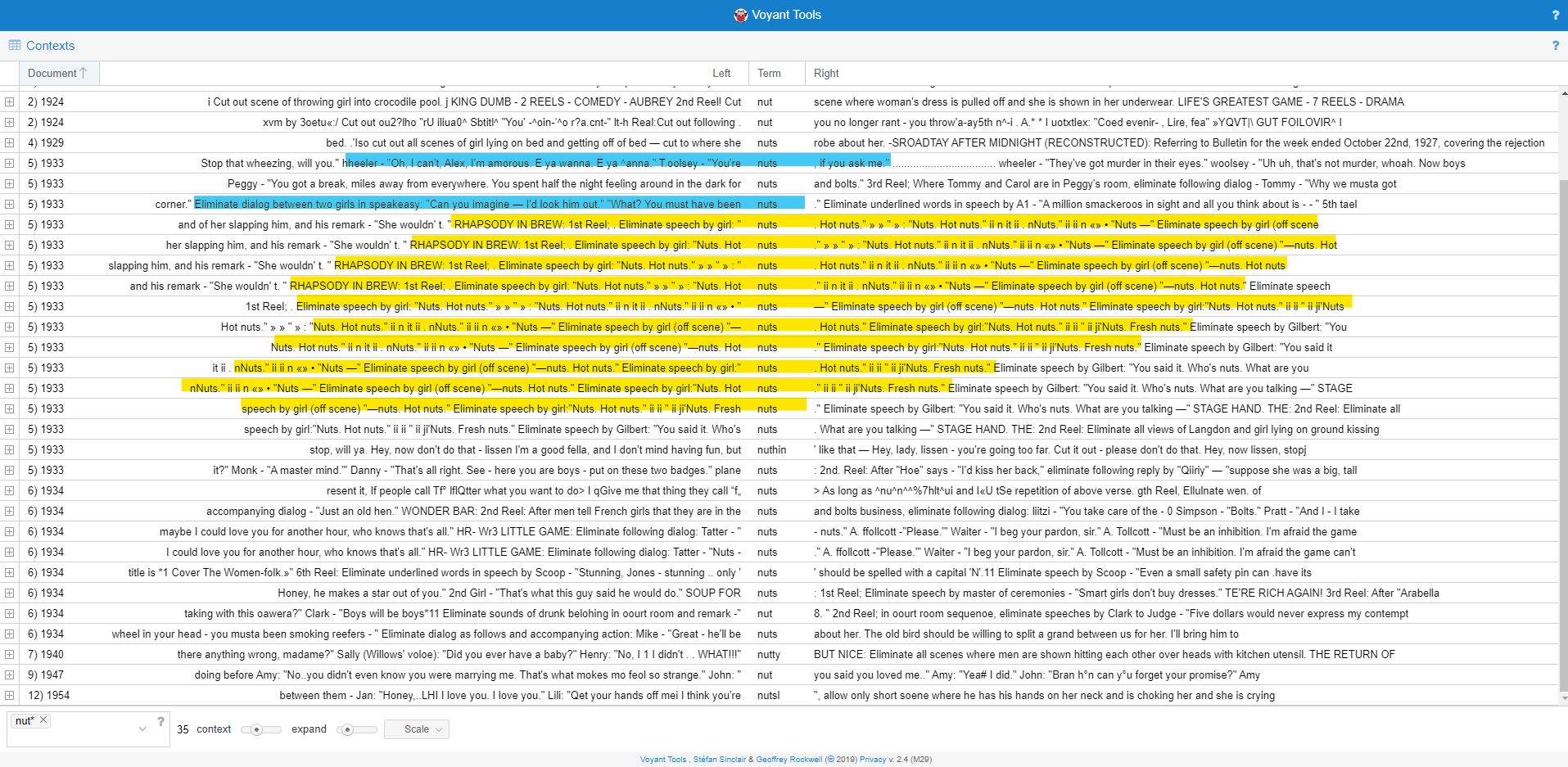

The final three topics explored in this section are Religion, Race, and the word "Nuts." These three examples are things that were an emphasis for the Board, but not prevalent enough to be considered a major topic. Much like crime, religion is difficult to search with just a few terms and what will be analyzed is the type of religious language censored and the contexts for the eliminations of religious figures from films. Race is a concept that surprisingly was not heavily censored by the Board, and the few examples of its appearance provide some insight into the possible motivations of the Board. Lastly, a specific example of a humorous type of censorship that is only loosely connected to the major categories - innuendo. In this case the censors adamantly were against comical dialogue involving the word: "nuts."

Beyond the bulletins, an important document for this analysis of Ohio's major topics is summary document found the collection of legal documents at the archive. It is unclear, but the document appears to be written by the Director of the Department of Education (and thus Chief Censor) Dr. Clyde Hissong in 1945 and was presented to an unknown group (there is a section listed as "extemporaneous and off the record" implying that it was a speech). Either way, the eleven page document, hereafter referred to as the Censorship Speech, describes the formation and function of the Board, including a section detailing some of the "standards of judging." This is not an exhaustive summary nor is it a guide, but rather it is a few talking points that note some of the specifics of the censorship process. As is stated in the document, "The standard for judging films is quite indefinite. The decision must be of a subjective nature. There is wide discretion left, therefore, to the film censorship staff to decide what should or should not be eliminated from a film" (Censorship Speech, 1945, Legal). The guidelines laid out in the Censorship Speech are to help guide the censors towards consistent decisions. Some of the major points to highlight are that the quality of the film or acting should never be judged, context within the film is vital to consider, and the continuity of plot must be respected. If these guidelines were followed then ideally the censorship of films would only remove "immoral" content while persevering the integrity of the film as a whole.

Alcohol

The Eighteenth Amendment was ratified in 1919 and prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcohol. Rather than limiting the consumption of alcohol, the Prohibition, as it came to be called, spurred on the public to drink in underground Speakeasies and cocktail parties. Bootlegging became a profitable industry and organized crime quickly capitalized on the opportunity for new profits. The Prohibition was one of the final major policy enactments of the Progressive reform movement (Tindall and Shi 1028-1033; 1079). The censorship boards of Ohio and rest of the country were formed as one of the many thrusts of the Progressive reform movement. While complex and diverse, the Progressives' goals were to hold society to a high moral standard, attempting to purge society of "social evils" (May, Screening, 45). On a deeper level, these Progressive reformers hoped to use movies as a tool for social reform, "As an amusement which could dramatize the reality of modern life, the movies became a prime conveyor of reformist goals. This centrally controlled medium might arouse the various groups and classes in the city to transcend their selfish interests in favor of a higher moral law" (May, Screening, 59). The trends tool below illustrates how the foundation of Progressive reforms and historical context influenced the topics of censorship.Figure 24: Trends-Raw: Alcohol

The trends above is the raw frequency data, showing that the bulk of censored alcohol content occurred in the 1920s during the years of the Prohibition. The Prohibition ended in 1933, explaining the decline. While the alcohol-related terms did not appear a significant number of times relative to other major topics, their significant appearance during this context illustrates their importance. Alcohol appears twice in the Censorship Speech. The first is as an example about dialogue, where it states "'Prohibition caused this' amounts to propaganda thrown into the story and is not a part of the forward-moving development" (Censorship Speech, 1945, Legal). The use of the Prohibition as an example further emphasizes the censor's feelings on the topic, even though this document was written over a decade after the Prohibition ended. The second example focuses on the content of the scene: "Degrading experience or emotion is not necessarily to be eliminated...For example: The D.T.'s in the Lost Weekend present powerful evidence for temperance. She Went to the Races - the drunken girl rolling off the couch with the man" (Censorship Speech, 1945, Legal). This example illustrates an exception to the general principle of censoring drunkenness. Not only does it support the claim that the Board routinely censored drunkenness, but it also is a significant statement about the Board's overall objective. As reformers their goal was to use their censorship to uplift the content of the films shown in Ohio so that society would progress to a higher moral standard. Their greatest fear was that these films would lead to the denigration of society's morals and standards.

Figure 25: Trends-Raw: Intoxicate

The censors were not only concerned with removing alcohol during the Prohibition, they also sought to remove any example of drunkenness or intoxication. This trends tool of raw frequency illustrates the censors' emphasis on the state of being drunk, independent of the context of the Prohibition. As seen in both the trends tools above, this was true throughout their entire history. One potent example of censoring drunkenness comes from a surprising film, Miracle on 34th Street (Bulletin for May 24, 1947, Bulletins). See the images below for the exact censored scenes (taken from archive.org).

Figure 26: Miracle 1

Figure 27: Miracle 2

This beloved 1947 holiday classic was censored for scenes early on the film where the gentleman hired to be Santa Claus in the parade is drunk. He is discovered by Kris Kringle (the real Santa Claus), who is indignant. In the censored scenes Kris exclaims, "You're a disgrace to the tradition of Christmas and I refuse to have you malign me in this fashion." Kris goes on to become Santa for the parade and in doing so is offered a spot at Macy's, thus setting up the plot of the rest of the film. Beyond the fact that is a widely loved and watched film that was censored, this example is interesting because it shows that even though the main character Kris Kringle villainizes alcohol and rebukes the drunk Santa, the censors still wanted those entire scenes removed from the film. If you were watching the film in Ohio you would have seen Kris Kringle arrive at the parade and then seen the head of the parade asking him to be the Santa Claus for the parade. These eliminations are not too jarring for the plot (as previously noted this was a concern for the censors), nor was Kris's rebuke strong enough for the drunk Santa to be an occasion for a moral example. Most likely the Board decided that these images of an intoxicated holiday figure would be too inappropriate for the masses of children who likely saw this picture in Ohio.

Crime

The Ohio Board was also affected by the fear that crime in films would lead to an increase of crime in society. In an internal document of the Board in 1928 there is a breakdown of types of eliminations for that fiscal year and that breakdown indicates that "tending to incite crime" was the most popular reason for an elimination (Statement of Films Censored, Dec 31, 1928, Rejected and General Correspondence). However, as mentioned previously, these categories of "indecent, inhuman, tending to incite to crime, immoral or tending to corrupt morals, sacrilegious, obscene," are as vague and far-reaching as the statue that formed the Board. It is impossible to say which censor compiled this information and how they chose to categorize it. With the categories and eliminations being extremely subjective it is highly probably that this data is inaccurate and misleading. It is even possible that the information is intentionally skewed in order to please the individual, public, or government entity to which the document is directed. Thus the search and trends of specific words, such as dancing and hitting, is a more reliable indicator of the real major categories of censorship, which would be sexuality, followed by far behind by violence, then alcohol, crime, religion, and race. For while crime was a concern of the public and the censors, there is not sufficient evidence that it was more important censored topic than sexuality or violence in films.

Trends - Major Topics Expanded

Figure 28: Trends: Major Topics Expanded

This trends tool shows all of the major topics identified previously a few additional that, while not having over 200 occurrances, are still rather significant. This tool is live and interactable, one suggestion to see a single term more clearly click on the term in the legend at the top of the tool in order to hide that term while maintaining the relevant lines of the other terms. Several of the additions fit the previous categories of violence or sexuality, but the two new ones are drinking and robbing, representing alcohol and crime. While at 164 for drin* and 139 for rob* these topics are not near the number of appearance of the other terms, they still are significant categories. With film censorship being a Progressive Era reform movement it is expected that there would be a connection between film censorship and the prohibition of the 1920s. Robbing fits into the topic of crime (or inciting to crime), something that was a stated concern of many censorship boards and the public at the beginning of the film industry. It was common for there to be newspaper articles, conservative books, and even police reports that argued that motion pictures were leading to an increase in crime and juvenile delinquency in children (Butters 9). In the Censorship Speech, a section describes how context and cinematography are important elements in censoring crime: "One view holds that the cord in evidence is suggestive of a method to use for a crime and should be deleted....The same view holds also for the silver cord as contrasted to any other cord would not be significant to youth as an idea for crime" (Censorship Speech, 1945, Legal). The first statement illustrates that when a cord for strangling is filmed in a certain way it could providing a sort of visual instructions for an individual wanting to strangle someone, while the second statement is supporting the first by stating that it is not the cord itself that it is a problem, but rather the way the cord is being filmed. This example supports the notion that crime was an important topic for censorship because of the fear that it would provide methods and motivation to youths.

The most likely reason for crime being at the bottom of this analysis is because of the separation between crime and violence in this research. In the MPPDA Production Code (1930), several acts of violence - such as murder, firearms, and violence with authorities - are covered under crime. While minor violence such as hitting and fighting are not included in the crime section of the MPPDA, most likely that is how the censors would have categorized it (MPPDA Production Code, 1930, Legal). While the MPPDA code was not produced by the Board nor is it known how often they referred to it, it is reasonable to suggest (particularly with multiple copies of the code surviving in the archival documents of the Board) that they were aware of the organization of its self-censorship demands. Thus most likely the Board considered violence to be apart of crime and not its own topic of censorship. For this research the separation is important because of the method of analysis relies on action terms that are better grouped as violence.

One of the categories explored in the close reading was "harming society," groups and actions that were a threat to the larger social order such as: bombs, mobs, riots, etc. In searching these terms in the larger corpus the results were rather underwhelming, with none of the terms appearing over 50 times. In searching for other action terms related to crime: burglar, rob, thief, steal, etc., only "rob" had a significant appearance - as noted previously.

Figure 29: Trends-Raw: Rob/Police

The trends tool above is a search for both rob* and police*, and the raw appearances illustrate a correlation between the two. While neither of these terms was extremely significant in the context of all of the censorship, the correlation above illustrates an emphasis on censoring scenes of crime on screen. For a more specific look at the censorship of a film for the reason of crime, see the case study on M.

Religion

Subtitles and Dialogue

Figure 30: Trends: Religion

Religion was not a major topic of censorship overall, rather the censorship of content related to religion fell mostly within the realm of subtitles and dialogue. The live trends tool above is showing raw frequencies, showing that despite a peak in 1924 and 1925, there was not significant change in the terms overtime. Rather these terms were censored whenever they appeared for the inappropriate use of them was considered sacrilegious. But sacrilege was confined to only dialogue and subtitles, rather it was also an issue in the presentation of religious individuals. In the Production Code of the MPPDA and the PCA (the enforcement division of the MPPDA), these terms were listed as profanity (MPPDA Production Code, 1930, Legal). While this may seem like one possible explanation for the decrease in the use of the terms "god" and "hell" after 1925, the Production Code was not introduced until 1930 and was not significantly enforced until 1933 when the PCA was formed. The decrease still could be a result of self-censorship, but more likely there is a connection between the shift from silent to sound films and the use of these terms. This is only a theory based on the trends above, and there are no hard documents to back this up. The more important point is that these terms were an emphasis of the Board's censorship efforts.

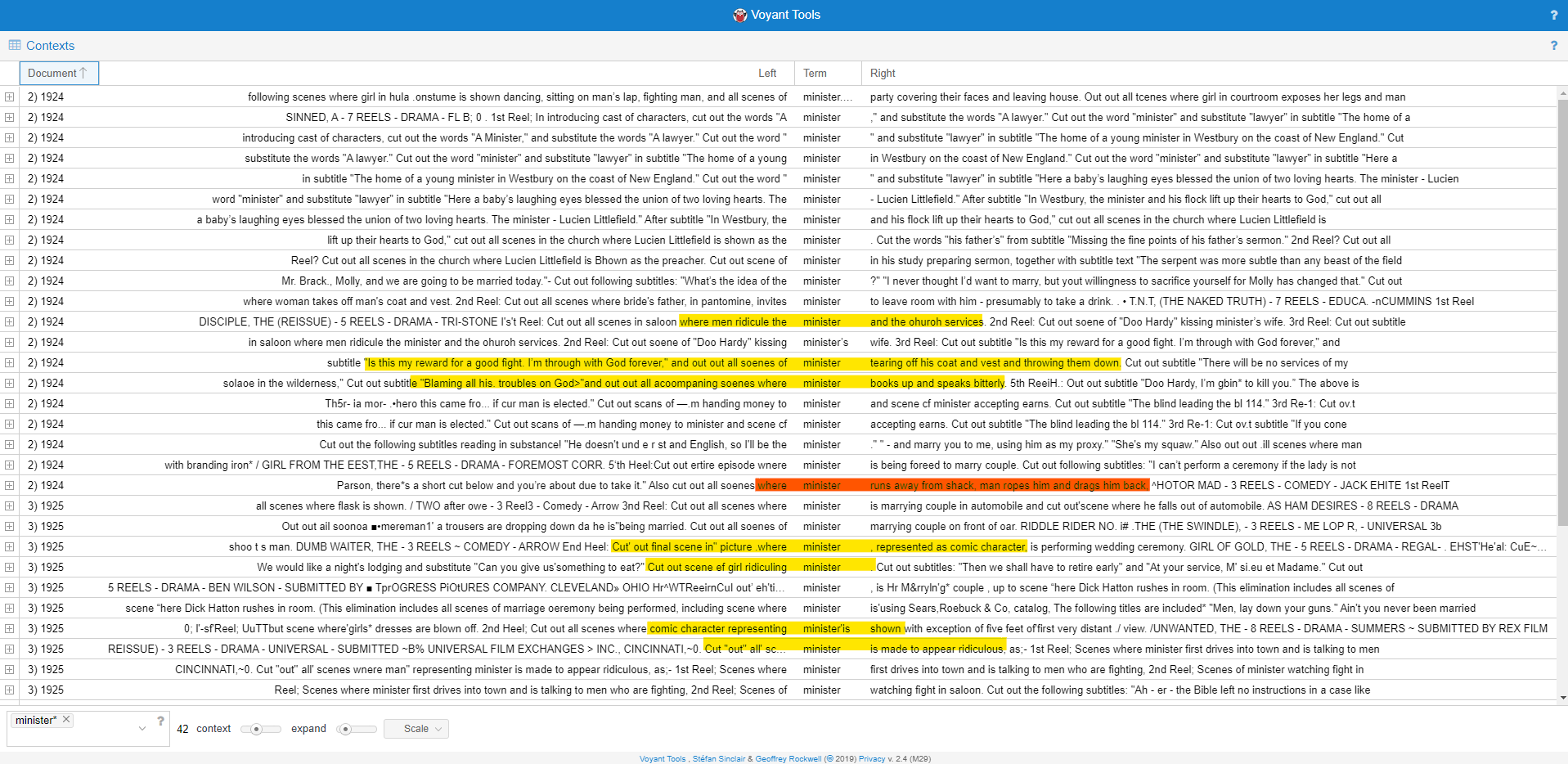

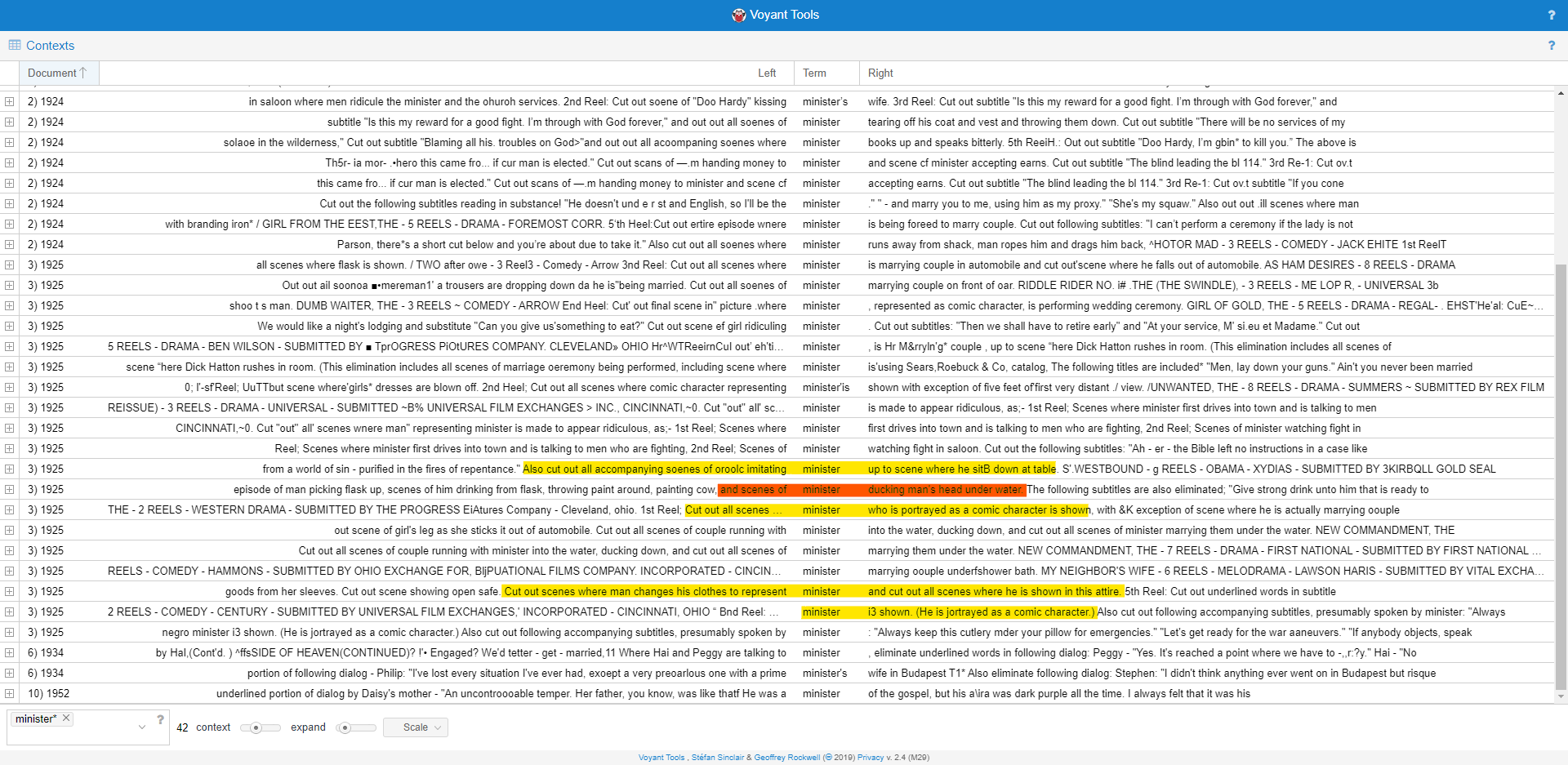

Minister

The first context tool below is an active embedded tool, the next two images are screenshots of that search with various results highlighted.

This is a live embedded tool, placed here so you can browse the results for "minister" or search for other terms.

Figure 31: Contexts: Minister 1

Figure 32: Contexts: Minister 2

Religious officials were not a major topic of censorship, rather it was more of an emphasis, as the Contexts tool above indicates by showing that there are only 42 occurrences of that term. Point 6 of the Censorship Speech states: "Ridicule of that which society respects. The clergyman may be comic or even dishonest, but it is not desirable to have the implication presented that the clergyman is not to be respected" (Censorship Speech, 1945, Legal). The two images are screenshots of the Contexts tool are highlighted to point out a couple of the situations of sacrilegious moments that were censored. The orange highlights show the few examples of violence being done towards the minister. The yellow highlights show instances where the minister is ridiculed or played as a comic character, and two instances where the minister tears his coat and forsakes his religion. What is interesting is that despite the statement of the summary document, many of the yellow highlight examples are because the minister was being portrayed as a comic character. Most likely this is due to the fact that those eliminations were in the twenties and the summary document was in the forties, but it also goes to show the subjective-ness of the censorship.

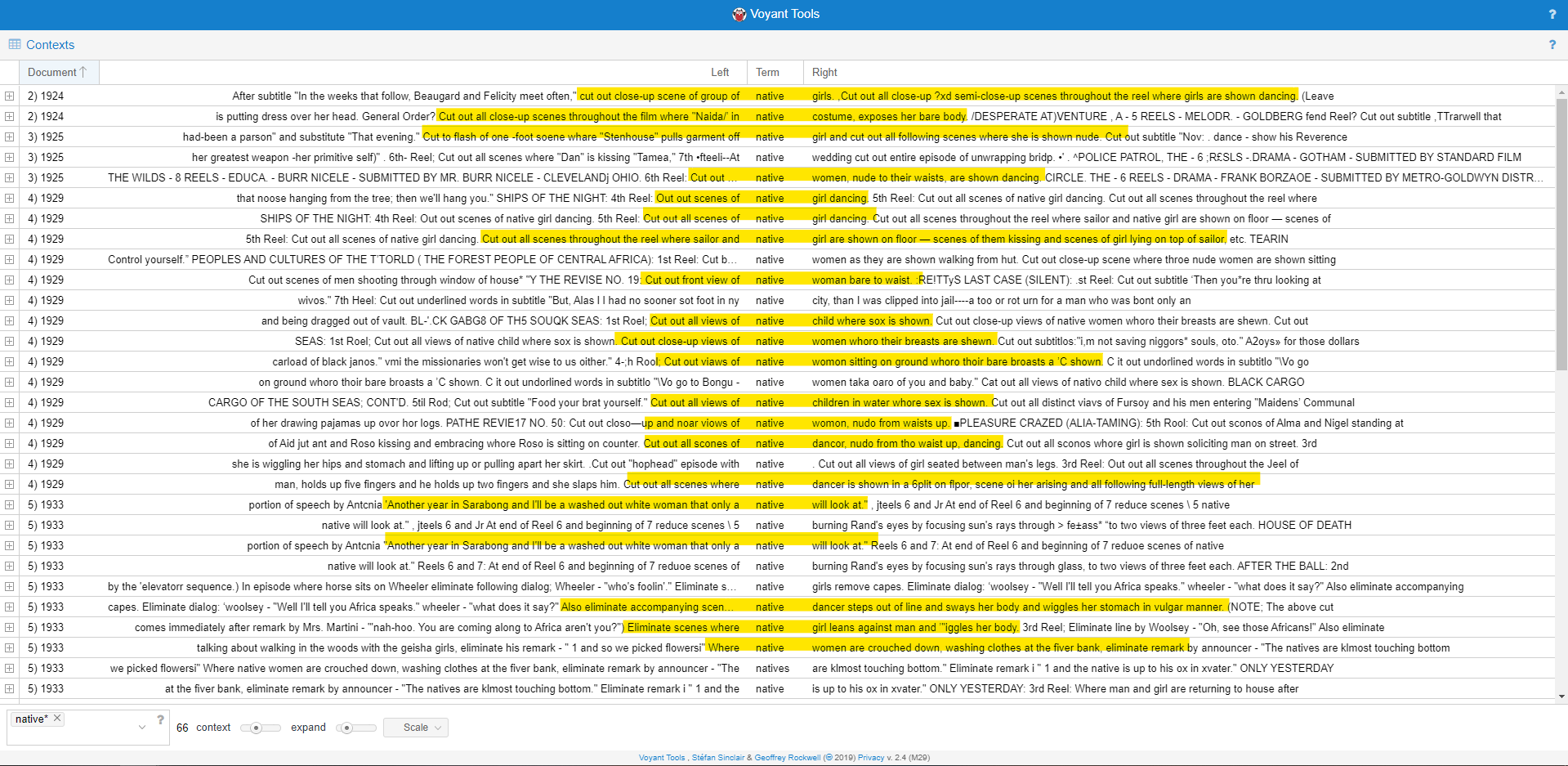

Race

People of color in film was not a major topic of censorship in Ohio by itself. A search of various racial terms had low yield, and most of them were in either violent or sexual contexts and not specific to the race being shown. In the Context tool screenshot below shows a sample of the search for the term "native." Highlighted are the eliminations that were sexual in nature, you can see that it is the majority of the eliminations listed. Additionally, a scan of the other instances of "native" shows that nearly every example involved some other topic for the elimination.

Figure 33: Contexts: Race

This censorship of race solely within context is important point to note, for while they only censored race in the context of the major topics of sex and violence, they also censored content that was racist. Ohio was one of the states to reject the showing of the 1915 Klan film Birth of a Nation due to its racist content, in Ohio the film was rejected over five times from 1915 to 1925 (McEwan 358). This lack of race-focused censorship was not true of all state censorship boards, "Virginia's state censors had a different, unwritten mandate - they were expected to keep from the screen any portrayal of an African-American that did not reflect current racial sensibilities - making sure that its moviegoers saw only false stereotypical African-American images: blacks as maids, butlers, fools, or criminals," (Wittern-Keller 29).

"Nuts"