Introduction

The Introduction to the Renaissance gardens of early modern England

The growth in the popularity of lavish gardens and the development of garden design in England can be attributed to the artfully designed gardens of Italy and France. Throughout the fifteenth century and continuing into the sixteenth century, Italians gardens experienced explosive growth, evolving into three different phases: Humanist, a the High Renaissance, and Mannerist garden styles. Like most major creative achievements there are prime examples of their splendor in other mediums such as painting and sculpture. By the end of the 1570s, Italy’s greatest wave of creative achievement in gardening had come to an end. However, in contrast, England had just begun to explore its creative abilities. The development of lavish gardens and architecture was a product of peace and prosperity. Tudor art and architecture matured slowly, as the new king, Henry VII, who came to the throne in 1485 did not indulge in profligate spending. Instead he consolidated his dynasty, focusing his efforts on financial thrift. Thus, England saw little expression of Renaissance art for the first twenty-five years of the Tudor rule [Strong, 1998].

The English Renaissance was a time of eccentricities and artistic growth that touched every aspect of English life. Originating in Italy the Renaissance movement expanded across Europe, this pan-European trend slowly took root in England, not becoming truly evident within English culture until the reign of Henry VIII [Ridley, 2002]. England saw great evolution in every art form, inspired by the trends popular in France and Italy. Renaissance pleasure gardens suffered from a lack of scholarship until very recently. The study of such gardens has grown in the last decade or so as they offer a unique window into understanding the concerns of Tudor monarchs, nobles, and gentry. These reflected monarchial wealth and power, encompassing the cultural values and social expectations of Tudor England [Woodhouse, 1999].

Historian Roy Strong examines the creation of these spaces identifying them as an art form and as an expression of royal iconography [Strong, 1998]. In his book Renaissance Gardens in England, Strong ties the birth of the Renaissance garden in England to King Henry VIII and his ongoing competition with King Francis I of France. Strong credits this competition with the massive expansion of Hampton Court Palace, the site of Henry VIII’s first garden. “The gardens however, were the palace’s most startling innovation…their design and layouts are of major significance of the whole development of garden design in England down to the accession of James I” [Strong, 1998]. The fundamental research and analysis of Strong serves as the foundation of this project, Creating Nirvana: The Renaissance Gardens of early modern England. This project seeks to understand the gardens of early modern England and their functional impact within English society [Woodhouse, 1999]. This is a multifaceted history that examines the intertwining of these whimsical exterior spaces and the underlying cultural factors that influenced the design and usage of these spaces. Through the analysis of major design trends and common artistic elements, this project will provide a useful understanding comprehension of this lost art form in all its practices and evolutions [Friedman, 1989]. This project illustrates that the designs and ambitions for these gardens shifted across time in response to the influence of Italian and French trends, but also as Tudor and Stuart monarchs first attempted to establish their own legitimacy as ruling houses and then became concerned with displaying increased order and prosperity. A discussion of the elements found within these ornate spaces expresses the values of early modern English society, with significant value placed on control, wealth and status. These spaces evolved as English society evolved, celebrating the wealth and abundance of a nation at peace and waning as the nation faced the dawn of a civil war. This evolution is evident in the analyzes of the popularized style trends, Heraldic, Mannerist and Eclectic, influencing these gardens throughout the early modern period.

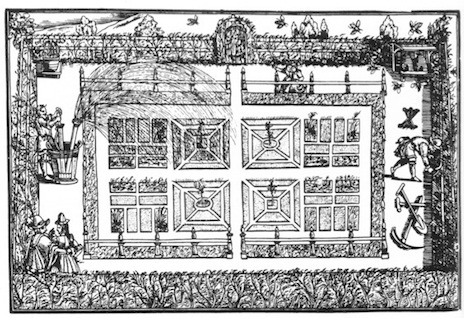

The Renaissance gardens of the European continent influenced English gardens through the adoption of important elements of design. The gardens of Renaissance Italy can be identified by their symmetrically planted designs, that created line of sight from the main house to smaller enclosed structures, sculptural elements and water features. In sharp contrast, the French formal gardens devoted emphasis on the arrangement of floral patterns rather than displaying harmony between the garden and existing architecture. The Italian ideals of garden design reached England during the second half of the fifteenth century; the innovative idea of relating the garden to the house and vice versa was the most significant element adopted within English garden practices. The Italian influence becomes evident in the brightly colored heraldic figures found throughout early English gardens. A common tread identified within Italian and French influences was the ground patterns created by detailed foot paths created by low hedges and other low growth flora coming together to create knots gardens and labyrinths. The origins of the compartments can be traced to the Villa de Medici, first being employed across Europe by the sixteenth century.  Garden designs shifted from raised beds and medieval turf beds to sectioned plots trimmed in hedges and rails. Wooden rails provided framework for herbs, fruits and climbing plants [Jacques, 1999]. The complexities of compartments grew as the popularity of knots gardens grew. A knot garden was a extremely formal, heavily manicured space designed in a square frame. Within these natural frames, often created by tightly controlled box hedges, a verity of aromatic plants and herbs were used to create elaborate patterens. These detailed and complicated features derived from embroidery patterns. Jacques references The Gardener's Labyrinth of 1577 which includes twelve interlocking knot designs. The image to the right is a prime example of the knot gardens take from the pages of The Gardener's Labyrinth of 1577

Among all of the elements present within Italian and French Renaissance gardens, geometric symmetry was one of the most highly prized [Jacques, 1999]. By the fifteenth century the concerns of Italian garden design shifted to increasingly to organization and the purposeful division of garden spaces into harmonious compartments. Historian David Jacques analyzes the Italian influence on the atmosphere and features of Tudor gardens in his article "The Compartment System in Tudor England".

Jacques focuses particularly on the division of spaces within Tudor gardens and their place within English tradition [Jacques, 1999]. Jacques focuses his research on a specific aspect of the Tudor gardens; he analyzes the complex geometric divisions of Tudor style gardens. Jacques considers the translation of the compartmented system in England from Italy and the rising popularity of this design trend during the sixteenth century. He argues that the compartmented system is better seen as a translation of a new concern for social order and harmony rather than a new vocabulary for garden features. [Jacques, 1999]. Jacques studies the makeup of different compartments and the fashionable trends of the seventeenth century that influenced the perceptions of these spaces.

Garden designs shifted from raised beds and medieval turf beds to sectioned plots trimmed in hedges and rails. Wooden rails provided framework for herbs, fruits and climbing plants [Jacques, 1999]. The complexities of compartments grew as the popularity of knots gardens grew. A knot garden was a extremely formal, heavily manicured space designed in a square frame. Within these natural frames, often created by tightly controlled box hedges, a verity of aromatic plants and herbs were used to create elaborate patterens. These detailed and complicated features derived from embroidery patterns. Jacques references The Gardener's Labyrinth of 1577 which includes twelve interlocking knot designs. The image to the right is a prime example of the knot gardens take from the pages of The Gardener's Labyrinth of 1577

Among all of the elements present within Italian and French Renaissance gardens, geometric symmetry was one of the most highly prized [Jacques, 1999]. By the fifteenth century the concerns of Italian garden design shifted to increasingly to organization and the purposeful division of garden spaces into harmonious compartments. Historian David Jacques analyzes the Italian influence on the atmosphere and features of Tudor gardens in his article "The Compartment System in Tudor England".

Jacques focuses particularly on the division of spaces within Tudor gardens and their place within English tradition [Jacques, 1999]. Jacques focuses his research on a specific aspect of the Tudor gardens; he analyzes the complex geometric divisions of Tudor style gardens. Jacques considers the translation of the compartmented system in England from Italy and the rising popularity of this design trend during the sixteenth century. He argues that the compartmented system is better seen as a translation of a new concern for social order and harmony rather than a new vocabulary for garden features. [Jacques, 1999]. Jacques studies the makeup of different compartments and the fashionable trends of the seventeenth century that influenced the perceptions of these spaces.