Visual Analysis

Garden Features

Heraldic style gardens were the first wave of the three garden treads seen in Early Modern England. Images of wild beasts adorned most every aspect of Tudor embellishments including the royal gardens. These depictions became yet another display of the Tudor monarchy's greatness, solidifying their claim to the throne and serving as a visual reminder of their dine right. Movement and drama are key identifiers of Mannerist gardens, not dissimilar to the paintings and sculptures created in the same style. Mannerist gardens lent themselves to theatrical display. This style evolution was heavily focused on the manipulation of water, with detail water features flowing through the gardens. The last trend to impact the elete and royal gardens of Early Modern England was the Eclectic style gardens. This trend stared the slow push back to a naturalistic garden space, less concerned with shows of power and dramatic theatrical display. These gardens were less elaborate focused on bring the confort of indoor lesure to the outdoors in the form of banqueting houses and grottos.

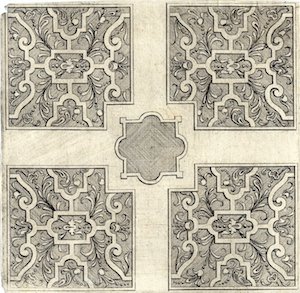

Knots

Knots were a central feature in all sixteenth century pleasure gardens, later replaced by the parterre de broderi, made popular in the Jacobean period [Roy Strong,40]. Parterre de broderi were a simplified versions of knots, characterized by low ground cover shaped into geometric sections connected by sandy paths. Within the interior of English gardens, raised beds evolved into the wildly popular, keynote feature referred to as knotted beds or knots. A standard knot is formatted into square beds, in which low box hedges form complex geometrical patterns. The negative spaces between hedges, often referred to as compartments, were filled with ornamental flowers including tulips and roses. The rediscovery of older novelties such as topiaries regained popularity [Biddle, 1999]. The practice of enclosing these highly stylized spaces with high walls was a common practice in the royal renaissance gardens. Trellises were used to make galleries, the enclosed walkways that connected various parts of the gardens [The English Garden, 2018]. Knot gardens were a major signature feature of Tudor garden design prized for being an example of perfectly controlled symmetry carved from the uncontainable wilds of the naturalistic world. The gardens mimicked the under-over movement of the threads used in needlework, marrying the intrinsic qualities of embroidery to the gardens of Tudor England. Knots were usually constructed on small scales with multiple heights at hedge intersections to mimic the overlapping of threads. Knot gardens were traditionally square in format, taking two forms, either opened knots or closed. Open knots were patterns cut out from low growing herbs such as creeping thyme, and dissimilarly colored soils, sands, or gravel [Strong, 1998]. The effect can be recreated with lavender or upright forms of rosemary. Bush forms of thyme such as Thymus Fragrantissimus and Thymus Vulgaris, as well as hyssop, cotton lavender, terbium, winter savory and golden marjoram would also work well and give a variety of texture and leaf color. Although requiring more frequent cutting, the haze of leafy green, gold and silvers creates a more embroidered look [The English Garden, 2018]. Closed knots filled their negative spaces with flowers of one color [Strong, 1998]. Most knots were edged with buxus, a sweet-smelling hedge plant with paths lined with fine gravel or sand. Knots were meant to be admired from afar, usually from the comfort of the king’s private apartment [Strong, 1998].

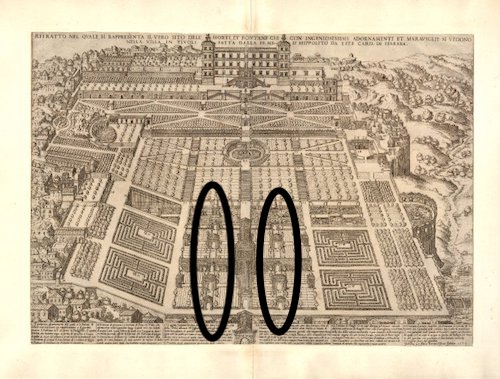

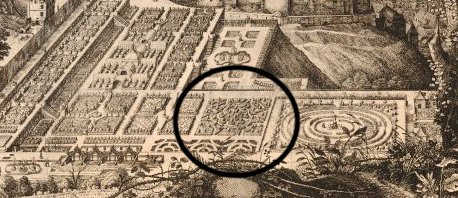

Mazes

These labyrinths evolved from knot gardens made popular in the sixteenth century, the tangled paths were an analogue form earthly struggles allowing people to make-light of the complexities of life [Woodhouse, 1999]. Mazes were constructed from dwarf box hedges due to their hardy nature. Despite the name these hedges grow above the height of the average renaissance man [Strong, 1998]. Maze gardens provide unique walking paths constructed out of puzzle- like entanglements made far more interesting with the addition of dead ends and false starts. The mazes at Hampton Court Palace serve as the longest living example of these labyrinths [Strong, 1998].

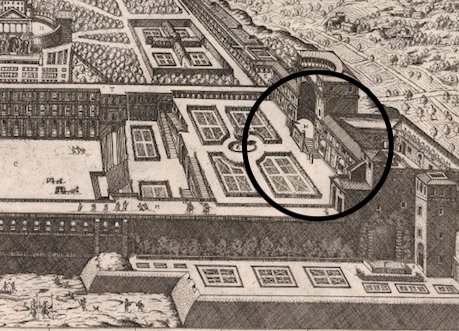

The Terrace

With the evolution of Renaissance style gardens came the marriage of exterior and interior spaces. The addition of terraces provided streamlined access from the house to the surrounding gardens. Pleasure gardens were often sunken providing expansive views of their detailed features from these terraces. Terraces were often broken up by walkways or ‘forthrights’ as they were commonly known [The English Garden, 2018]. These fourthrights formed patterns that grew in complexity and became more elaborate.

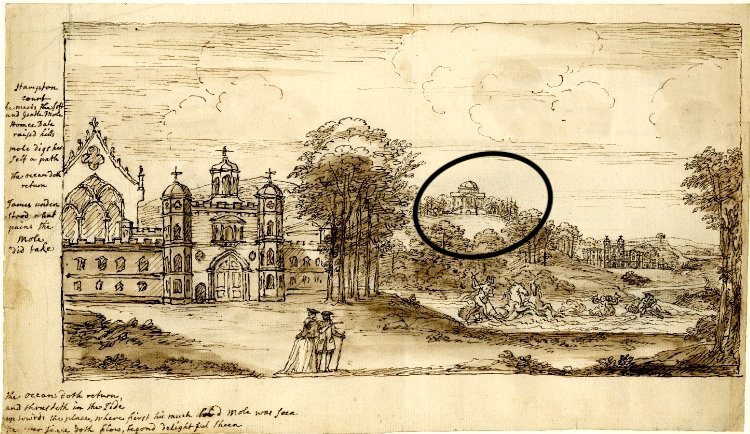

Tudor Mounts

Developing from earthen mounds, a popular design element of thirteenth century gardens, Tudor mounts transformed the landscape form flat planes to elevated venues from which surrounding terraces, water features, patterned gardens, groves, orchards and woods could be admired. These mounts were planted with fruit trees among other types of trees. Foot paths wandered to the top of this elevated plots lined with fragrant herb and other types of sweet-smelling foliage. Arbors of trelliswork adorned the top of these mounts usually draped in with climbing vines [Woodhouse, 1999]. The presents of man-made earthen mounts have been a feature in English gardens since the Middle Ages, remaining popular beyond the sixteenth century. Mounts provided an open plane within the layout of formal gardens, creating height to relatively low spaces that were visually pleasing to the garden’s visitors. The ascending and descending of these mounts gave visitor multiple perspectives in which to view the gardens below. Henry VIII displayed his princely magnificence with a series of active architectural developments. Again, the gardens of Hampton Court Palace serve as a prime example, “…he built a palace and surrounding gardens that would demonstrate the legitimacy of the House of Tudor as the ruling family displayed by their heraldic beasts populating the gardens” [Woodhouse, 1999]. The first formal mount to be created at Hampton Court Palace was the “Mount Garden”, built in 1529, a rectangular plot enclosed and located adjacent to the entrance gate. Brightly colored heraldic beasts adorned the path leading to the top of the mount, where elaborate arbor, adorned with a gilded crown, awaited to provide shelter to exploring patrons. Heraldic beasts were a display of a family’s status and power, the king commissioned mount that these beasts adorn, emphasizing his power and the virtues embodied in the heraldic beasts.

Water features

Tudor gardens were rich with symbolism, mostly conveying the power and wealth of the monarchy. Water was prized as a powerful force with the ability give and destroy life; the ability to control such a force opened the door to many possibilities. Water was used with in English gardens to create drama, movement, and narrative. Creators of these spectacles drew upon popular the Italian narrative. The English harnessed these narratives for imagery, which took form in numerous fountains. The subject- matter moved from Christian religion to glorifying allegorical gods, goddesses and monarchs. The fountain at Kenilworth gardens portrayed scenes from Ovid’s Metamorhoese within the detailed carving Neptune, Thetis, Triton, Protheus and Doris, a visitor to the garden familiar with Ovid’s work wrote this about the fountain “…’Heer were things ye see, moought looking'; his mind must have wandered to Thetis, as her dolphins, not as portrayed on the fountain '”[Woodhouse, 1999].

Groves

Elizabethans were in some ways still pursuing the medieval or, hortus conclusus (enclosed gardens), but now it was in the Renaissance pleasure gardens that became symbolically associated with the Virgin Queen, Elizabeth I. In describing the grove of Diana at Nonsuch Palace, Watson alluded to the association with Diana, huntress and virgin... “Most powerful Diana claims all the magnificence and glory of the place as her own; let us pray to her for that enjoyment of everlasting honour and service to the state, and most happy memory, on which the far-seeing hero, Lumley, in the course of another history than this, set his heart” [Woodhouse, 1999].