Camp Morton in Memory

As the larger picture of Civil War prisons is looked at, it becomes noticeable that some prisons have certain strengths that have allowed them to be more easily remembered, studied, and widely publicized over other prisons. These strengths usually relate to primary sources that are useful to the memory of these prisons, and often come in different forms. The first type of primary sources are those that come out of the prison: namely records and diaries. The records that were kept and accumulated throughout the Civil War were placed together in the War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (here after referred to as the Official Records). This multi-series bound copy of all records from the Civil War is widely used by historians to look at, study, and scrutinize every aspect of the war, including prisons; however, there is always the issue of missing records. While most all prisons appear to have complete records for the entirety of their existence, and most secondary works on Andersonville, Elmira, and Libby cite the Official Records, Camp Morton is missing several months of records, of varying type, including medical, during the year 1862, and often records are incomplete. Therefore, for several months, there are no Official Records to help understand or know what happened at Camp Morton. Below are two excerpts from the Official Records, one is detailing an escape attempt, the second, an inspection report.

Private James E. Pierson, Company H, Forty-third Kentucky [Indiana] Infantry Volunteers, being duly sworn, on his oath says: I was on duty at Camp Morton on the night of September 27, 1864, on post Numbers 42. Shortly after 8 o'clock I saw a number of rebels run from the barracks toward the end of my beat. They had ladders which they set against the fence and began to climb up the ladders for the purpose of escaping over the fence; there were about fifteen or twenty. They had four or five ladders. One of them when he was straddle the fence said that, by God, he was all right. I shot at him, when he exclaimed, "O Lord," and fell back inside the fence. By this time there were three others on the fence, who escaped before I could reload my gun. I made a thrust at one of them with my bayonet as he jumped from the fence. I cannot say whether I hit him or not. As the prisoners left their barracks, I heard one of them exclaim, "Come on, boys." I ordered them to halt, but hey paid no attention to it and came on a double-quick toward the fence. Several shots were fired by the adjacent sentinels; I should think about eight. The night was very dark.

COLONEL: I have the honor to report that I have during the week ending October 15, 1864, inspected this camp, and I have found the barracks, kitchens, and the grounds kept thoroughly policed every day, and the general health of the prison is greatly benefitted by the thorough policing and exercise the men are obliged to take in policing the grounds of the camp. Clothing and bedding have been issued to all destitute prisoners, with the exception of shoes, of which a sufficient quantity has not yet been received. Rations issued by the commissary of subsistence for the camp have been in compliance with orders, and potatoes have been issued every day during the week at the rate of eight ounces to each man. The two new wards of the hospital building are about completed and will be ready for use in a few days.

While these two reports do not contradict or give a detailed insight into the daily life of prisoners at Camp Morton, these excerpts show how beneficial the Official Records can be to studying Camp Morton. However, it is also obvious that these records and reports are washed fairly clean of any personal insights into the camp.

Diaries and Correspondence

The second primary source coming directly out of the prisons are diaries and correspondence. Correspondence comes with its own problems since most prisons limited the number of letters prisoners could send, receive, and how many lines could be written per letter. Also, it eventually became normal practice to read the letters in order to make sure no negative comments escaped. This means that looking at correspondence coming out of the prisons from prisoners is not always a valid way to understand the prisons. However, diaries prove to be a very good source, since there is no indication that they were censored. Diaries from the prisoners come in many forms: diaries that have been directly transcribed and published such as the diary of Eugene Forbes, who was held at Andersonville, and Curtis R. Burke’s diary, who was held at Camp Morton for a short time. While these diaries sometimes provide valuable information and recount events that are crucial to understanding how a prison operated, often they can be difficult to read depending on the level of education the writer had. In addition, sometimes these entries leave out background information on individuals and events, which can leave the reader confused.

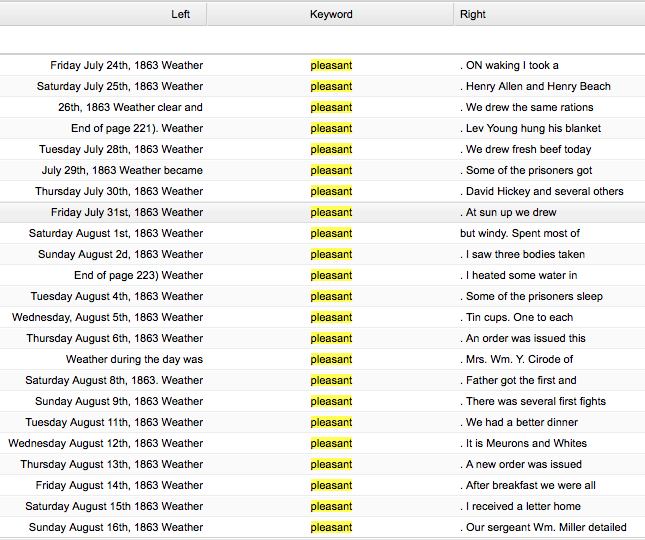

Below is a list of the world “pleasant” used in the diary of Curtis R. Burke during his stay at Camp Morton. While Burke was held at Camp Morton for twenty-four days, and used the word “pleasant” twenty-four times in his diary during this stay. Not placed in context, pleasant is one of the main words in his diary entries during those twenty-four days. However, as you can see below, when the word “pleasant” is placed in the context which Burke used it, he is only speaking about the weather.

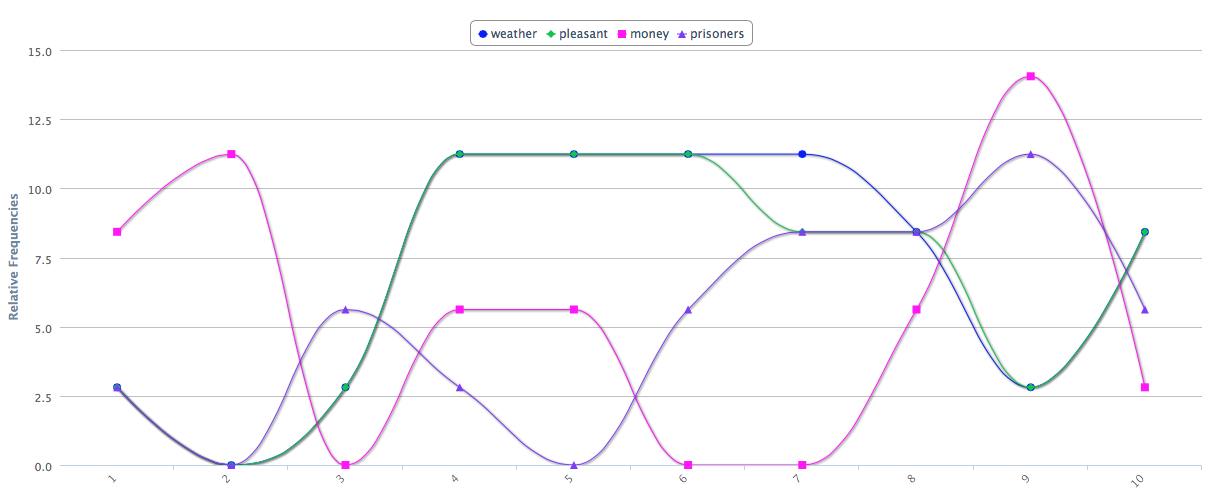

Knowing how a word is used is only as useful as knowing how many times it was used. In the visual below, you will see that the world "pleasant" was used twenty-four times by Burke in his diary while at Camp Morton. In addition, he used the word "weather" twenty-five times, "prisoners" eighteen times, and "money" nineteen times. While understanding the context in which "pleasant" is used is important, viewing the number of times it was used in relation to other words adds another layer of context, and puts the word use into further perspective. While Burke frequently commented on the weather, he did commented on other areas of his day just as many times.

There are also diaries that have been heavily edited and annotated, leaving only the most sparse of information, or can include insights into the prison, what was happening during a specific entry, as well as information on other prisoners. These works include the diary of Arthur G. Sedgwick and the diary of First Lieutenant George R. Lodge, held at Libby Prison. These diaries also have positives and negatives. These diaries have the added benefit of having context added after the fact, either by the writer himself or by the editor. However, the writer might recall events differently after the fact, and editors are taking on the role of assuming what the writer meant or felt. While this is a sampling of the diaries that are products of Civil War prisons, there are few from Camp Morton. Diaries are often considered some of the best primary sources on Civil War prisons because prisoners are writing directly after events, and are not recalling from memory later on.

Memoirs

Memoirs, on the other hand can be uncertain sources because memories can change over time, and can be affected by time, the memories of others, and changes in how societies would view specific memories. In the work, Haunted by Atrocity, Benjamin Cloyd points to embellished memories coming out of Andersonville in the post-war years, and the issues they have created. In addition to complete works of memoirs that are written after the war, there are sources such as articles written for magazines after the war. These are usually small articles written by veterans of the war and/or survivors of prisons. These pose their own set of issues, not entirely different from complete memoirs. These articles are often much like memoirs in that they are written some time after the event(s) occurred, so they cannot always be reliable. However, these short articles often only recall one small event, or can sum up a man’s overall experience over a given amount of time. There are many of these articles in Confederate Veteran magazine, and while many of the articles are interesting and can provide valuable information, some of them do not vary in content.

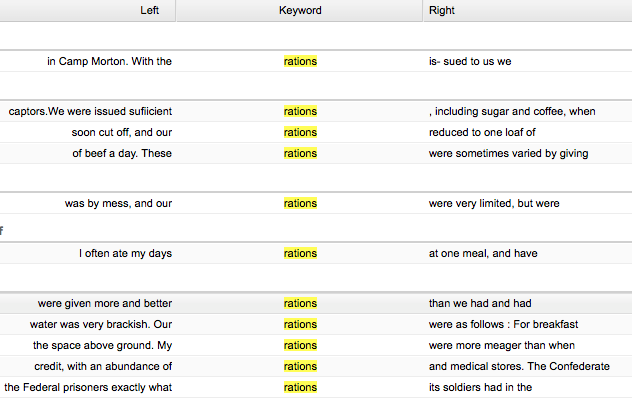

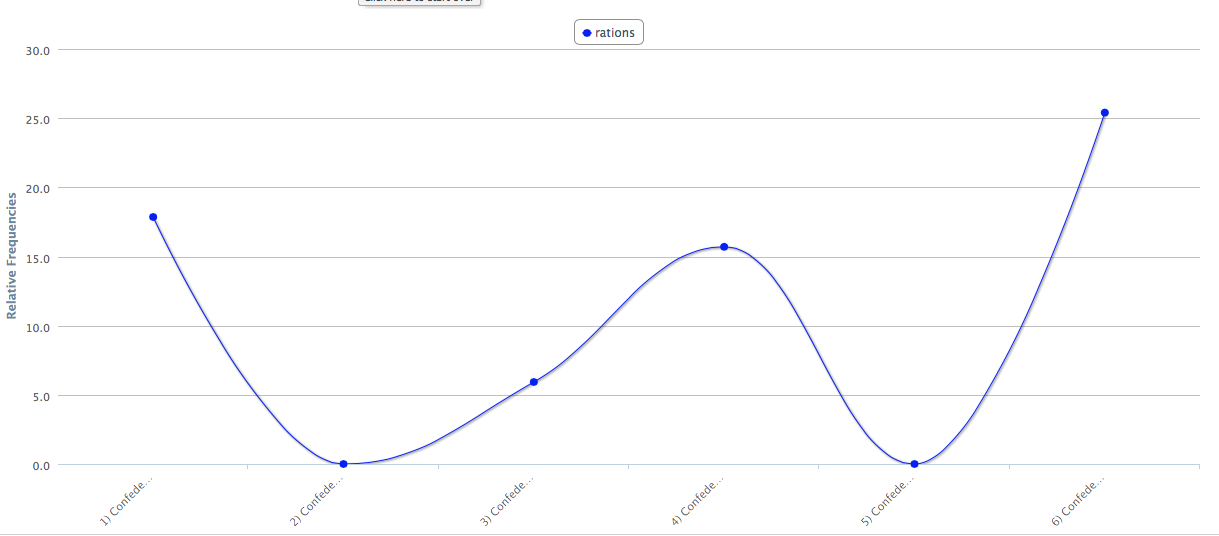

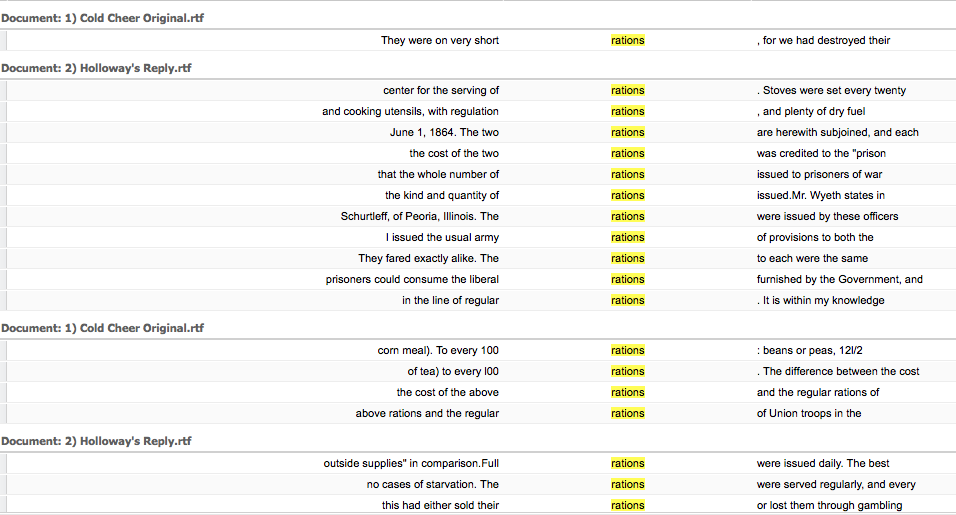

Below is the use of the words "rations" in a series of articles written in Confederate Veteran magazine by former Camp Morton POWs. This table shows the different ways in which the word "rations" was used. Keep in mind that these articles were all written after a significant amount of time, and therefore are can be classified as memoirs. The next image shows that "rations" was used sixteen times total between the articles, but the table also shows how many times each article used the word. While one cannot tell how the authors ranked the importance of rations during their imprisonments, one can see patterns in the word frequencies and word usage.

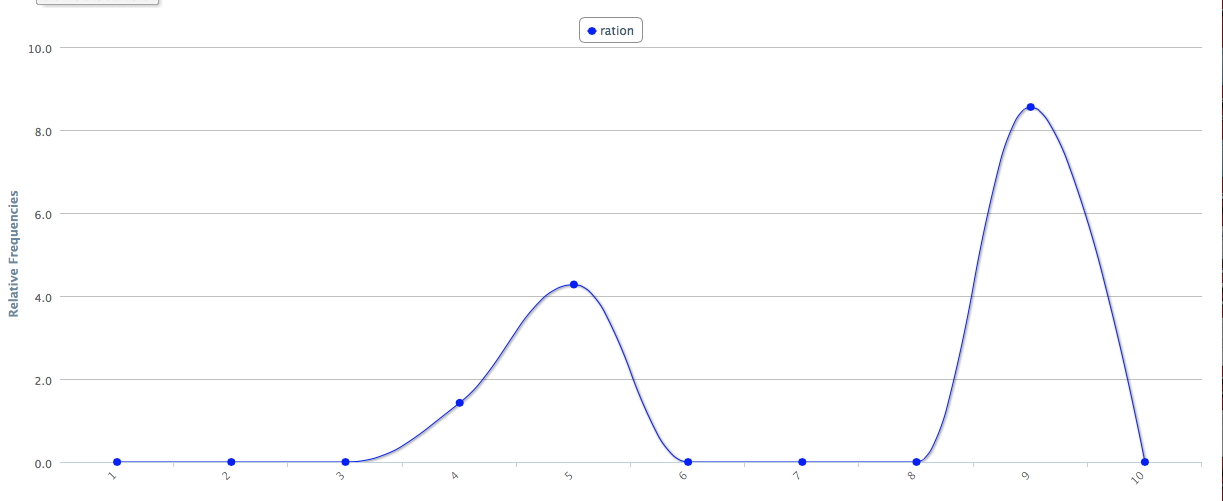

This table below also shows the use of the word "rations," only in two separate articles from Century Magazine. The first article, "Cold Cheer at Camp Morton" was written by Dr. John A. Wyeth, a former POW of Camp Morton. Wyeth tends to have more negative connotations with his use of the word. The second article, "A Reply to 'Cold Cheer at Camp Morton," was written by W.R. Holloway, who refutes most of what Wyeth said in his article. Holloway's use of the word tends to have more positive connotations. Both Wyeth and Holloway's use of the word can be compared to how the word was used in the Confederate Veteran articles. The next visual shows the word "ration" being used ten times in Wyeth's original article.

Newspapers

Another primary source that is important are those that were written about the prisons, most notably newspapers. Local newspapers frequently published articles about the local prisons, the prisoners, and events that took place inside, and anything about the prisons that would affect the local citizenry. Some secondary works rely heavily on these works not only for information, but to validate diaries, Official Records, correspondence, as well as information coming from the citizens outside. While most all prisons had local newspapers writing articles, one prison in particular, Elmira Prison in New York, had multiple newspapers writing about it: Elmira Daily Advertiser, Bangor Daily News (Maine), Rochester Daily Union and Advertiser, Elmira Daily Advertiser, Elmira Star-Gazette, Elmira Sun-Telegram, New York Evening Express, New York Evening Post, and even the New York Sun and New York Times, as well as many more. While not all prisons have lists of local newspapers that can provide primary sources, all that exist provide an important insight. Local papers in Indianapolis frequently published articles about Camp Morton and its prisoners. Some historians contribute to the eventual fall-off of articles published about Camp Morton as the result of the local citizenry becoming bored with the prison and prisoners.

Finding newspapers relating to Camp Morton from the time that it was open can be an exhausting experience. However, the below sample of text from W.R. Holloway's reply to Dr. John A. Wyeth that was discussed above. In Holloway's reply he used several sources to support his own words, some of these being newspaper articles from the Indianapolis Journal.

The " Indianapolis Journal" of January 2, 1864, stated:

There was a rumor that several of the union soldiers belonging to the veteran reserve corps, who were guarding the prisoners at Camp Morton, were frozen to death on the night previous. Governor O. P. Morton requested General H. B. Carrington, United States Army, then on special duty in this State, to visit all of the camps and hospitals in and around the city, to inspect and report as to their condition and the amount of suffering that had resulted from the intensely cold weather. The following is an extract from his report:

"Troops on duty, the Invalid corps, Colonel Stevens. No deaths or serious injury from the extreme cold. All reports to that effect are without foundation. The guard is relieved hourly, and as much oftener as the soldier advises the corporal by call that he suffers in the least. Hot coffee is served to the men when relieved, and pains are taken to prevent suffering and needless exposure. . . .

"Among the prisoners there is less sickness than usual. I visited nearly every barracks and the hospitals. The men were cheerful and thankful; in fifty letters sent out nearly every one spoke kindly of their treatment. One prisoner said to me,' It would be extravagant to ask for anything else.' Seven hundred extra blankets and many shoes had been issued. They lacked for nothing indispensable to their personal health and comfort."

While the article was merely relaying a report by the United States Army on the extreme weather conditions and the suffering that it caused, it shows how newspapers can be very important not only in shaping how the citizens of Indianapolis viewed the POWs and even guards during the war, but perhaps most significantly, what was left for later citizens to learn.

Summary

There are other primary sources coming from outside and inside of the prisons. These include correspondence of prison guards, commandants, governors, and many others who were directly or indirectly involved with the running of the prisons, those coming from prisoners as well as Official Records are often looked for or at first. These primary sources provide valuable information about prisoners; however, when they no longer exist, or never did exist, they can create large gaps in information that is vital to not only research, but also to the memory of Civil War prisons.

Despite the primary sources and the memory theory, Camp Morton is a Civil War prison that has been largely forgotten. In the above paragraphs, the primary sources from prisoners, newspaper articles, and even the Official Records of Camp Morton have been discussed. However, there are also other works that detail the hardships of Camp Morton and use even more sources. The memoirs of Dr. John A. Wyeth, published in 1914 spends an entire chapter detailing the horrors that Dr. Wyeth experienced while at Camp Morton. Wyeth details the lack of heat in the barracks, lack of food and the fight against starvation, and even malicious cruelties experienced by some prisoners and witnessed by him. There are also works such as James R. Hall’s Den of Misery, which focuses on the bad years of Camp Morton, and uses Dr. Wyeth’s memoirs, and also only one diary, that of John Franklin Champenois. It is at this point that one of the main reasons why Camp Morton has been so easily forgotten comes to light: lack of primary sources, especially diaries.

As the text and visuals show, the remembrance of Camp Morton has depended on will always depend on more than monuments and arguments - it depends on solid sources that can be used. All major events in history that are studied at great length are studied with sources of all kinds. There are written documents, images, fossils, artifacts, and even prehistoric paintings on the walls of caves. Camp Morton is lacking in this area. While there are letters and diaries that came from Camp Morton, they are not of great value, with little usable information. Local newspapers, while starting out strong, eventually slowed reporting on the prisoners. This lack of primary sources coupled with the Camp Morton’s lack of notoriety greatly contributed to it being forgotten.