Monuments to Camp Morton

While the history of Camp Morton and the movement of the POW bodies is interesting and intriguing, these monuments exist in a world filled with monuments concerning different aspects of the American Civil War, as well as the social, cultural, and political changes that have occurred since and those that will continue to occur. While many of these monuments permanently fill public space, they have been questioned, studied, scrutinized, and commemorated for over a century. The study of monuments has been expanding for some time, and many works have focused on the Civil War.

Over time the citizens of Indianapolis have had different memories: memories of the Civil War, memories of Camp Morton, memories of the exhumation and reburials, and memories of the monuments being dedicated. The memory that exists of these events, people, and objects also functions within history (Brown, 2004, 7-8). These memories add to the history of the American Civil War, as well as the history of the camp and the history of the commemorations of Camp Morton in Indianapolis, and the history of Indianapolis as a city and as a living space.

Monuments also represent more than just the event or people that they were erected to commemorate. They have the ability to represent the issues surrounding those people or the event, both then and in the present. This is represented in the six assumptions of memory, all of which affect not only history, but also how the past is understood and perceived. First, memory is activated by present concerns, issues, or anxieties; second, memory narrates shared identity; third, memory does not have to remember events exactly, but merely embrace what is deemed worthy of preservation; fourth, memory is partial, partisan, and contested; fifth, memory relies on material and symbolic support; and sixth, memory has a history. (Dickinson, Blair, and Ott, 2010, 6). These six assumptions can be applied to the monuments around Indianapolis in various ways.

For example, the monument at Crown Hill Cemetery represents all concepts, thoughts, and feelings that the individuals who erected it associate with the deceased prisoners. The monument at Crown Hill is more applicable to this theory because it was erected through the work and dedication of citizens, whereas the monument that now stands at Garfield Park was originally erected by the United States because of a law regulating all Civil War veterans had properly marked graves.

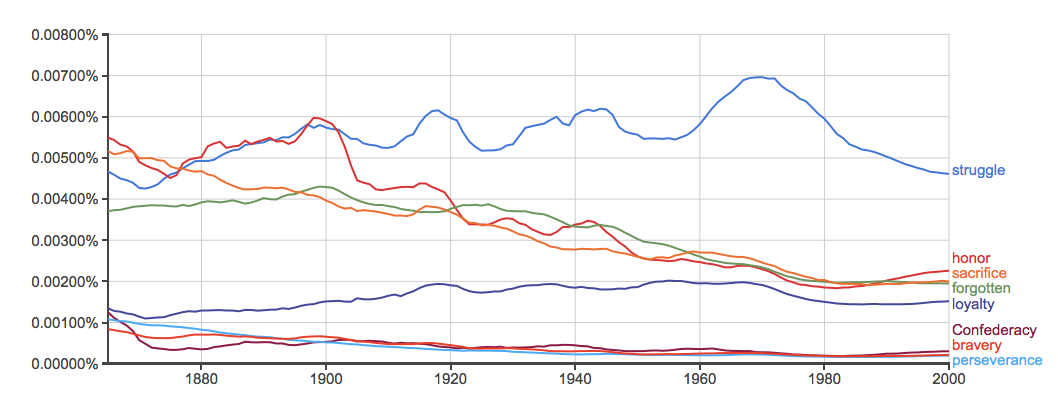

Monuments can encompass many different aspects of a society or culture: issues of nationhood, race relations, gender roles, cultural norms and the continuity of those ideals (Brown, 2004, 18). What is most important is that often times those aspects are believed to be continued throughout the erection of monuments. While the monument at Crown Hill Cemetery may or may not be representative of this theory, mostly because it was erected more than a century after the war - some may see it as a continuation of ideals often placed on soldiers, especially those who died while in prison are acceptable to these feelings, because these men died. However, this is not necessarily the case. The Google Ngram below shows the frequency of words often used in relation to POWs and Confederate soldiers from 1865 to 2000. As you can see, only a few of the terms show an increase around the time of the first and second monuments being placed at Crown Hill Cemetery.

The ideas and aspects that a monument can represent are often not those of an individual, but of a group of people, a collective memory. Collective memory is often placed at the center of remembrance, showing the power of a group compared to the power of a single individual. Groups often have the same memory or feelings about a given aspect of their past or culture. However, it should be noted that while a collective group is often more powerful than an individual; individuals with similar memories and feelings often form the collective group — collective memories start with the individual.

Monuments such as the ones that stand at Garfield Park and Crown Hill Cemetery are considered war memorials because they represent an aspect of war: prisoners and death. War memorials pose their own issues, but unlike other monuments, war memories often represent the politics and culture of the time they were erected. For example, the monument erected originally at Greenlawn Cemetery, but that now stands in Garfield Park was erected in 1909. The main reason for this monument being erected was that a new law passed forcing all Civil War graves to be properly marked, if possible. While this law was passed and the monument was erected more than forty years after the war ended, this was still a healing time for the United States. However, it should be noted that not all war memorials are representative of this theory (Mayo, 1988).

To some, monuments are considered “infrastructure” and are defined as the physical objects that come out of memory, and allow people to engage with the past. This means that monuments, including those in Indianapolis, have the ability to speak of and for the public; that they are built as representations and keepers of memories, and are a way to disseminate memory to everyone, whether or not those people agree with or share the memories (Dickinson, Blair, and Ott, 2010, 10). With the multitude of Civil War monuments and other historical marks dotting the landscape of the Untied States, there are bound to be issues. Many view monuments as objects that either misrepresent history, or that are incorrect in their inscriptions and commemoration all together (Loewen, 1999). While it is not the job of this author to say weather or not the monuments and markers standing in Indianapolis fall into this class of monuments, however it is this author’s job to make all aware that this belief does exist. What is most argued about monuments such as these, is not what the inscription reads, but that they exist at all, especially since most memorials and monuments “can possess enormous power and influence,” and are often used to “impress and claim” certain ideas and issues “in visibly public contexts” (Doss, 2010, 9). Many feel that as Confederates who died as prisoners of war, these individuals do not deserve the right to be remembered, yet as Confederate prisoners they have a place in enemy memory, the memory of these men does live on. This situation is compounded in the subsequent generations by mass culture in the form of cinema, museums, and even monuments that can change not only an individual’s view of history and that individual’s memories about the past, but also change their present, future, politics, and subjectivity (Landsberg, 2004, 2). This point is very important to those who wish to keep specific memories and views on the past a certain way, but feel that they may be challenged by monuments from differing standpoints.

In addition to the lack of diaries and journals, there is also the issue that the city of Indianapolis grew bored with Camp Morton and its prisoners. They soon began to look past the prison camp, ignoring it, and therefore little record was left. How individuals or societies remember does not just concern written statements and published works, but it also includes memorials, preservation, parades, days of remembrance, and so much more. While the locations of some Civil War prisons have been preserved and heavily memorialized such as Andersonville; others have fallen by the wayside such as Camp Morton. Nothing today is left of Camp Morton, mostly because the city of Indianapolis never again became interested in it or its prisoners. Even after the war when over one thousand Confederate POWs had to be buried within the city at Greenlawn Cemetery, reburied within that cemetery, and then reinterred once again in another cemetery, Crown Hill Cemetery. Monuments were raised by a few interested citizens, mostly in accordance with Federal Law, but they are mentioned little in newspapers, and ignored by many. Therefore, for the most part, Camp Morton and the 1,616 POWs who are now buried in Indianapolis have been forever forgotten. A playground and homes now sit atop where the prison camp once was. Four small corner markers mark the boundaries of the camp; most of them overgrown in weeds and grass. The monuments that stand in remembrance are scattered across Indianapolis. Nothing stands in memorial at the original location of the cemetery that was used for the 1,616 who were buried (some bodies were sent home to families); that monument is on the other side of the city, in a completely unrelated location. There is a monument that stands over the graves now, but only because one is required by Federal Law, and a few dedicated citizens.

As can be seen throughout this section, the monuments to Camp Morton and the POWs that died there have played an important role in Indianapolis since the ending of the war, despite the lack of knowledge about it today. This quite possibly the most interesting part of the history of Camp Morton — that it had such a rich and interesting story after the war, yet it almost completely unknown and the monuments ignored despite their sizes and locations.