Army

Changing faces of the U.S. Army during and after the American Civil War.

Before examining how the military viewed their role in the West, it is important to understand some of the changes that took place in the American Military following the Civil War. Prior to the American Civil War the American Army was relatively small. The U.S. Army had five mounted units in 1861 when the war began that numbered no more than three thousand men and were poorly equipped at the start of the war. During the American Civil War hundreds of thousands of men served in the Union volunteer units while the Regular Army slowly increased. At the onset of the war in 1861, the two Regular Army Cavalry regiments that had been fighting in the West against the Indians were kept from the battlefield as politicians attempted to fight a “Volunteer War.” The politicians in Washington preferred to use volunteer troops to fight the war rather than the limited regular army units available at the time (Longacre, General John Buford, 75). As such the Volunteer Army grew dramatically in size and outnumbered the Regular Army regiments substantially. At the end of the War in 1865 there were 959,460 men reported serving in the Union forces while the Regular Army forces were restricted by the government to number no more than 41,819 (Secretary of War. "Report of the Secretary of War."Message of the President of the United States to the two Houses of Congress. (H.Rpt. or S.Rpt.) 1865). In the war's aftermath the government had to address this and reorganize both the regular and volunteer armies. Many men were discharged from service, others joined the regular army, and the federal government authorized increases in the number of cavalry regiments. In Hedren's Great Sioux War Order of Battle he raises an interesting point in his examination of Army Officers in the west at the time. Hedren examines the military careers of many officers, including those of Custer's famous 7th Cavalry, and shows that a large majority of officers in the West had either combat experience in the Civil War or American West fighting Indians. Of these officers many also had received temporary promotions for valor on the battlefield. This is important to note when examining the Army following the American Civil War because many of the officers in the Volunteer Army who had proven themselves on the battlefield took positions in the Army following the War and were sent to the West. This section will further contextualize and examine the changes to the U.S. Army following the war and display statistical evidence in the form of graphs and charts that illustrate these changes. The graphs below are made from evidence gathered in the Secretary of War Reports from 1863 to 1877 to Congress. If any of the visuals below do not load, please click on the visual's title to open a PDF file of the image, or go to the Sources page where all the visuals for this project are listed on the left hand side of your screen. Please take note that images of the Voyant tools are not interactive like the imbedded web tools.

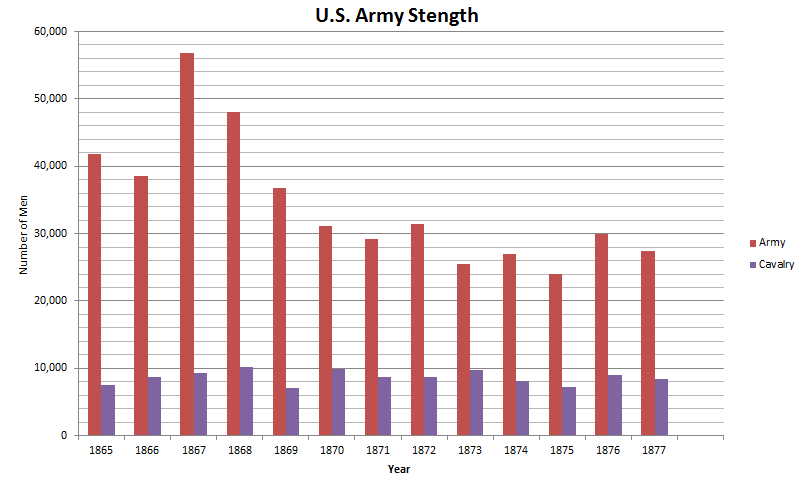

Figure 6: Army and Cavalry Strength Compiled from the Secretary of War Reports 1865-1877

Army and Cavalry Strength following the Civil War

During the American Civil War the Union Volunteer Army became a military force the size of which had not yet been seen on American soil. In 1863 the Union Army was reported at to have 918,191 men in service. That number dropped in 1864 to 860,737 but increased again in 1865 reaching its peak totaling 959,460 men in service in all Union forces (Secretary of War Reports 1863-1865). At the end of the War the government authorized the increase of the U.S. Army regular forces to 41,819, of which 7,512 men were allocated to the 6 cavalry regiments at the time. In the time following the war it is important to understand that the military was downsizing from nearly one million men across all forces to only forty two thousand. This created numerous logistical problems and ultimately was a task that took two years to complete. Many of the officers who had proven themselves in the war moved into the regular army, including George Custer. The efforts to downsize the military can be seen in the Army Strength graph above. With the exception of 1867 and 1876 there were no large increase to the U.S. Army's size and in many years their force decreased. Throughout this period the cavalry increased in numbers up to 1868. In Figure 6 the changes in strength to the Army and the cavalry is shown. Figure 6 shows there are few instances when the cavalry lost numbers, however the years that they did also correspond to years that the cavalry were actively pursuing Native Americans on the plains and were engaged in Indians Wars (in 1869, 1874, and 1877 the specific wars and details about them can be seen on the Timeline page.) The cavalry arm of the U.S. Army consisted of five under strength regiments in 1861 and by 1865 had more than doubled in total number of men. A more detailed view of the cavalry regiments and equipment is examined in later graphs. As the Indian Wars continued the cavalry remained between seven to ten thousand men while the army itself fluctuated from around thirty thousand men for most of this period. As can bee seen in Figure 6, during this time the cavalry made up between one fourth to one third of the Army. Comparatively in the years before the Civil War the cavalry made up only one eight of the Army (Prucha, 390). This evidence shows how the views of the cavalry changed at least among political leaders and how the value of the cavalry as an instrument on the plains was being recognized.

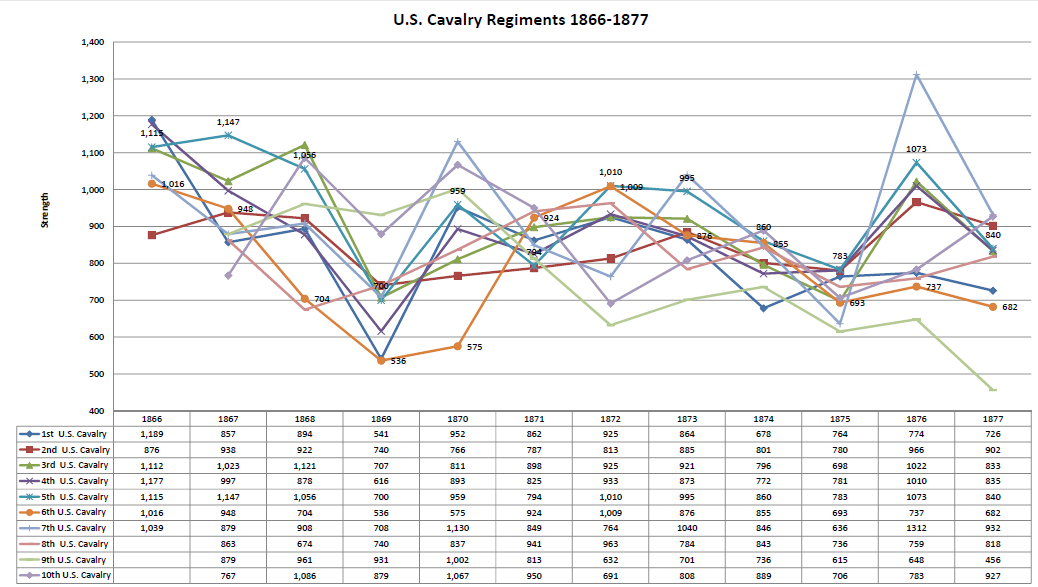

Figure 7: Cavalry Regiments Strength 1866-1877 Compiled from the Secretary of War Reports 1865-1877

Cavalry Regiment Strength changes from 1866-1877

In Figure 7 above the reported yearly strength for each of the ten U.S. Army Cavalry regiments is displayed. These are the reported numbers according to the Secretary of War reports to the U.S. government. In 1866 the 8th, 9th and 10th Cavalry regiments were authorized for creation by Senate and did not have reported sizes. This being said the majority of these regiments were deployed in the American West between 1866 and 1877. This graph illustrates how the man power of these units was impacted year to year from casualties (typically as a result of engagements with the Native Americans), desertions, and men whose enlistments ended and were discharged from the Army. The 4th through 10th Regiments fought heavily on the Military Division of the Missouri throughout this time. Again the influx in size mirrors periods of active wars like Sheridan's campaigns of 1868-1869, The Red River War 1874-1875, and the Great Sioux War 1876-1877. During these periods of declines it is interesting to see that there are often large influxes following them. George Custer's famous 7th Cavalry is one example of this. In 1869 the regiment numbered just over seven hundred and by 1870 had gained an addition four hundred men. Similarly in 1875, it numbered only six hundred and thirty six and by 1876 had more than doubled to just over thirteen hundred. While all of these regiments experienced a period of increase and decrease during these years, it is interesting that large influxes of men occurred in periods following large campaigns by these units on the plains. This raises questions relating to why this happened. Was cavalry recruitment prioritized during this period to replenish those losses? Where more men interested in joining the cavalry because of the way they were portrayed in the news? What factors played a role in these increases?

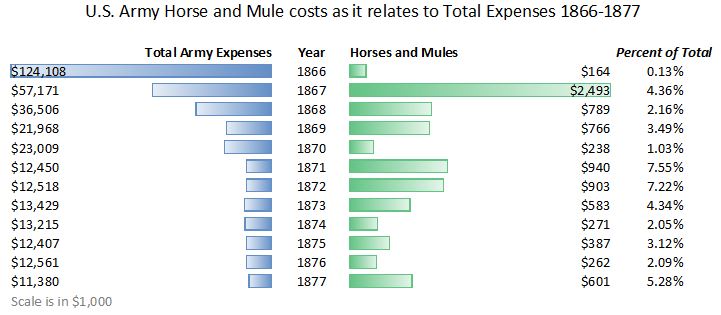

Figure 8: US Army Expenses Compiled from the Secretary of War Reports 1866-1877

Changes in the Army Budget

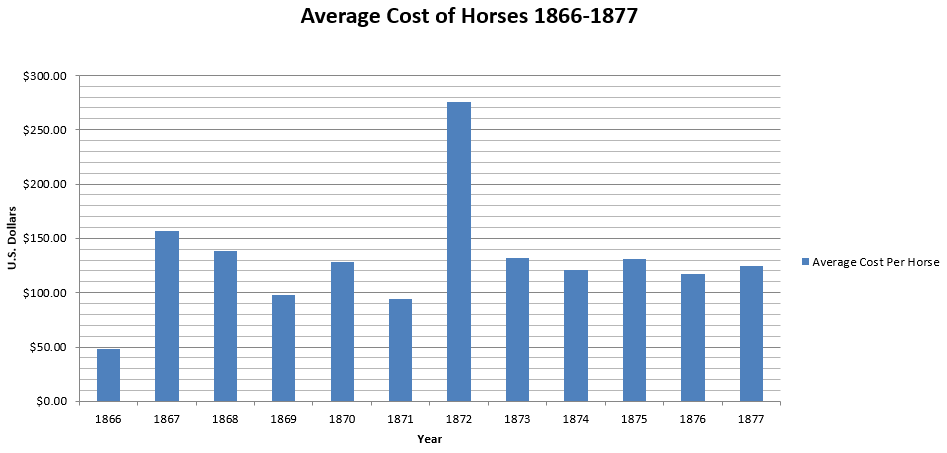

As the Army downsized following the American Civil War, the organization and structure of it changed as well (which was shown in Figure 6). As a result of these structural changes there were logistical changes as well which can be seen in Figure 8. This graph breaks down the Army's total expenditures between 1866 and 1877 compared to the figures reported by the Secretary of War that the Army spent on the purchase of Horses and Mules for the U.S. Army during this period. While the cavalry had many other expenses besides their horses, it is difficult to obtain exact numbers on what was spend on other supplies for these units. As such, since the cavalry would not be the cavalry without their horses examining the amount spent on their horses shows a portion of what was being allocated to the cavalry forces. Furthermore the cavalry soldier's most expensive piece of equipment besides potentially his rifle was his horse, therefore by examining the cost of the horse this examines the primary expense for the government to supply a cavalry soldier. A more detailed view of the cavalry expenses can be see here Total Cost of Horses 1866-1877. The "Total Cost of Cavalry Horses 1866-1877" graph shows a detailed view of the cavalry expenses shown in Figure 8. Figure 8 is scaled down to provide a better visual representation of these expenditures. The numbers that are shown are scaled in $1,000 and are representative of the value of the U.S. Dollar in the represented year. So in 1866 the U.S. Army spent $124,108,000 for the fiscal year. These expenses include everything from the payroll, to paying for building repairs and supplies, to paying off contractors and in some cases debt from the previous year. Comparatively there was only one year in which the value of horses and mules purchased for the year exceeded one million dollars and that was in 1867 when almost $2,500,000 of horses and mules were purchased. Below are more detailed examinations of the horses and mules purchased in these years. The majority of these horses were prioritized for use by the cavalry regiments on the plains. The detailed graph of cavalry expenses shows that in 1871 the majority of the expenses were for mules and less than two hundred thousand was spent on horses where in 1872 over nine hundred was spent. In the report of the Secretary of War in 1872 the Quartermaster General of the Army recommends that every year one third of cavalry horses should be replaced. The expenses in 1872 more than quadrupled those of 1871 because not enough replacement horses were purchased, leading to this recommendation by the Quartermaster General. This graph is important in showing the how the budget for these expenses changed over time. As the Army's budget leveled out in 1871 to around twelve million dollars and stayed around that point for the next seven years, the expenses for horses as well began to level out and continued to take up between 2-5% of the total budget. This is a dramatic increase from the 0.13% of the budget that was allocated to purchasing horses for the cavalry following the war and further illustrates the change in military opinions toward cavalry. Only twenty years prior to this the Army could not receive the funding for more than three units of mounted men and in 1867 were able to spend $2.5 million on horses for cavalry. Similarly to the number of men in the army, there are periods of influx that correspond to historical events. In 1871 the expenses for horses jumped dramatically which potentially correlates to the end of the campaigns of 1868-1870 and a desire to replace the horses that were used during that time. Throughout the period examined in this graph there are dramatic changes in the cost of horses and mules while the Army expenses overall slowly level out. This raises questions relating to why these numbers change so much which are answered in the graphs below.

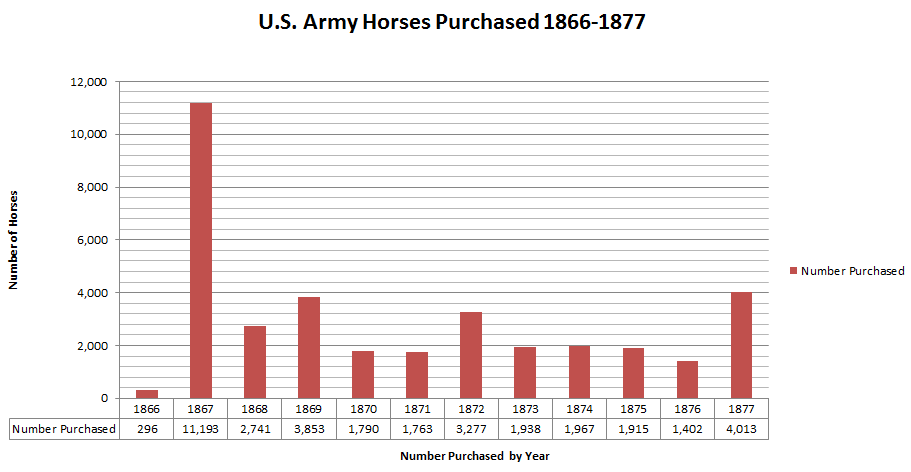

A Detailed Look at Cavalry Expenses: Where was the money going?

In Figure 9 and Figure 10 above the horses purchased by the U.S. Army between 1866 and 1877 are examined in more detail by showing not only the total number of horses purchased during each of these years but also by showing the average cost in U.S. dollars at the time per individual horse. it is important to note that the vast majority of the horses and money spent in these graphs are for cavalry horses. Artillery horses are included in these numbers but often made up less than 10% of the horses purchased and the total cost. Figure 9 depicts the dramatic changes that took place during this period. In 1866 following the American Civil War, the Secretary of War reports noted that the Army still had so many horses on hand from the war that few were needed to be purchased. As a result only 296 were acquired. Furthermore this was a rare year in which the U.S. Army made more money through the sale of horses in their possession than they spent on new horses. Following this, in 1867 there were more horses purchased than in any other year. Buying eleven thousand horses in 1867 compared to the average of 2,400 the following ten years dramatically changes the total costs as can be seen in Figure 8 where the total expense for horses and mules in 1867 was close to $2.5 million. This was in part because the quality of horses remaining following the Civil War that were in service but also because how few replacement horses were purchased in 1866. Following 1867 there is again a similar trend that the number of horses purchased increases around the time of military campaigns. Sheridan's Campaign of 1868-1869 and the Great Sioux War of 1866-1877 both were followed by increases in the number of horses purchased in 1869 and 1877, the two highest years following 1867. The increase from 1871 to 1872 is in part because of the recommendations of the Quartermaster General that one third of cavalry horses be replaced yearly as discussed in Figure 8. Throughout this twelve year period the average price of a horse was around $134. This number does include both cavalry and artillery horses, which were often cheaper than cavalry horses. Regardless these numbers show the average amount being spent on horses that were primarily sent to the plains for the cavalry. In some years the average cost was lower, like in 1866 when only 296 horses were purchased. This lower cost was also in part because the Army had so many horses available. The increase in average cost in 1872 and number of horses purchased is in part because the Quartermaster General and the Army attempted to replace more horses than they had in the past as well as acquire higher quality of mounts. This led to an increase in the price of each horse but also shows that a larger investment was being made into the cavalry arm of the Army during the 1870s. These numbers show various trends in the spending of the U.S. Army during this time on cavalry horses but ultimately show a shift in military spending that favored the cavalry and supplying them with adequate horses.