Early Career of Philip H. Sheridan

Early life, the Civil War in the West

Philip Henry Sheridan was born on March 6, 1831 in New York to Irish Catholic immigrants and was raised in Somerset Ohio. In 1848 Sheridan was accepted to the United States Military Academy where he struggled as a five foot four Irishman who got into fights. Sheridan would be suspended for a year because of his violent confrontations with fellow students. Sheridan graduated in 1853 34th in his class of 52 students. Sheridan would receive a commission in the Army as a brevet second lieutenant and was assigned to the 1st U.S. Infantry Regiment at Fort Duncan, Texas. After a short time in Texas, Sheridan moved to the 4th U.S. Infantry at Fort Reading, California. Most of his was in the Pacific Northwest, during which he participated in the Yakima War and Rogue River Wars. Sheridan gained experience in combat, was wounded once, and acquired both diplomatic and military experience with Indian tribes. Sheridan was promoted to Captain just before the American Civil War began (Morris, 15, 28-37).

At the start of the Civil War, Sheridan was made a commissary officer in Southwest Missouri managing supplies. While he excelled at this job, Sheridan desired a combat post and received a commission in the Volunteer army as a Colonel in the 2nd Michigan Cavalry in May of 1862. By July he saw his first combat at the Battle of Booneville where his seven hundred and fifty men routed four thousand Confederates. His actions gained the attention of his commanders, including General William Rosecrans, who recommended him for promotion. In Rosecrans’ letter sent to Washington recommending him for promotion, Rosecrans said "The undersigned respectfully beg that you will obtain the promotion of Sheridan. He is worth his weight in gold" (Hutton, Phil Sheridan and His Army, 12-14). By December of 1862 Sheridan was a Brigadier General leading the 11th Division, Army of the Ohio, at Stones River where he held back the Confederate assault and established a strong defensive position for the Union forces. This action won Sheridan another promotion to Major General. In six months Sheridan had risen from the rank of Captain to Major General. Sheridan continued to serve out west and fought for a time under General Grant. At the battle of Chattanooga in November of 1863, Sheridan led a break out charge which won him recognition from Grant and other superiors. Because of these actions, when Grant received command of all Union forces he selected Sheridan to command the Union Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac (Grant, 368).

Phil Sheridan, Major General of Volunteers, Union Cavalry Corps

In April of 1864, Sheridan arrived at the Army of the Potomac and found the Cavalry Corps in poor condition. His men were spread out on picket duty guarding the entire Union Army. At this time his force consisted of three divisions commanded by Generals James Wilson, Alfred Torbert, and David Gregg, numbering upwards of 10,000 men. Wilson had never commanded men in the field; Torbert had lead infantry and was often ill and unable to command, while Gregg was the only true cavalry general with any experience. Sheridan wanted to use this force aggressively in the Overland Campaign of 1864 and as a result would be sent with the the Union Cavalry Corps on Sheridan’s Raid. Early on in the raid, Sheridan found success capturing Confederate supplies and freeing Union prisoners. As Sheridan marched on Richmond, he encountered J.E.B. Stuart and the Confederate Cavalry at Yellow Tavern on May 11th. The Battle of Yellow Tavern was the first large engagement of Sheridan's Raid and Sheridan's first experience commanding large groups of cavalry. Sheridan launched multiple attacks against Stuart at Yellow Tavern using dismounted infantry tactics cavalry charges to break the Confederate position. In the end Sheridan drove Stuart from the field. During this battle General Stuart would be mortally wounded. The Union cavalrymen suffered 625 casualties, captured 300 Confederate prisoners, and recovered 400 Union prisoners (Kidd, 281).

Sheridan and his men withdrew from Richmond, fighting their way across Meadow Bridge and reached General Butler's forces in the South. The Cavalry Corps returned to the Army of the Potomac on May 24th of 1864. Sheridan's actions gained the praises of General Grant and Meade. Upon their return, Meade reported “On the 25th, the Cavalry Corps rejoined the army, Major-General Sheridan having successfully accomplished the object of the expedition for which he was detached" (Official Records, Volume 36, Part 1, 193). For the first time in the war, the Union Cavalry were used as an offensive threat to the enemy and found success using mobile infantry tactics in an offensive capacity. Sheridan and his fellow officers priased the cavalry's actions. As Kidd put it “If there were any honest doubts as to the efficiency and fighting qualities of the Potomac cavalry, they were dissipated by the campaign of 1864 (Kidd, 307).”

Phil Sheridan Commander of the Army of the Shenandoah, Major General United States Army

Following his exploits in the Wilderness Campaign Sheridan was entrusted by General Grant to take command of the Army of the Shenandoah. Confederate General Jubal Early had set out into the Shenandoah Valley with an estimated 12,000 Confederates attempting to invade the Maryland and distract Grant from his siege at Petersburg. In response General Sheridan was given command of the "Army of the Shenandoah" which consisted of three Union Corps and the Union Cavalry Corps numbering around 40,000 men. Sheridan was ordered to pursue the Confederates and prevent an invasion of the North. Sheridan's efforts against Early were slow at start. However, Sheridan led his forces to victory at Third Winchester and Fisher's Hill using his large cavalry force to great effect. While he was away from the army, Sheridan's forces almost suffered a terrible defeat at Cedar Creek. However, Sheridan arrived at the battle in time to rally his men and win the day. Sheridan's command of this campaign won him praises from Grant and President Lincoln as well as a promotion to Major General in the Regular Army, making him the fourth highest ranking man in the Union forces (Morris 258, Hutton Phil Sheridan and His Army, 12-14). His successes in the later half of the War not only propelled Sheridan through the ranks of the Army but also caused him to emerge from the Civil War as the most prominent Cavalry officer in the United States Army.

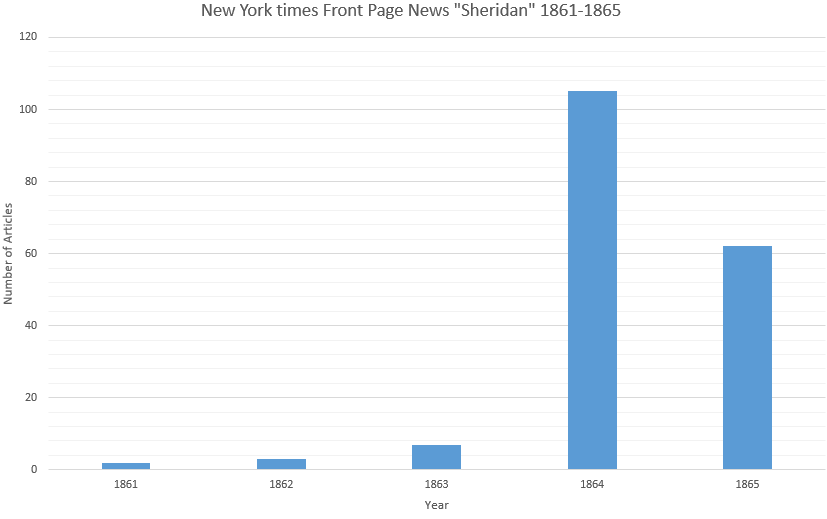

Figure 3: Search Results Sheridan On the Front Page of the New York Times

During the Civil War Sheridan was not relevant in the news until he took command of the Cavalry Crops in 1864. Above Figure 3 shows the number of front page newspaper articles published by the New York Times during the American Civil War that had the name "Sheridan" in them. As it shows, the New York Times had over one hundred front page articles containing his name in the year of 1864. This is more than likely influenced by the commands given to him and the battles his forces took place in. As the war came to a close in 1865 the number of front page articles containing his name dropped, however there were still over sixty articles. These results show how often Sheridan, and often the cavalry, were being reported to the public. While it is not an unprecedented number of articles, it is enough to infer that Sheridan was a well known and influential figure during the last years of the War. The extent of this will be further examined in the text analysis portions of this project.

Sheridan in the West “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

In August of 1867 General Grant appointed Sheridan head of the Department of the Missouri, relocating him from his reconstruction duties in Texas following the Civil War. Sheridan replaced General Winfield Hancock at the Department of the Missouri who had failed to control the Sioux and Cheyenne in his unsuccessful campaign. This would be the beginning of a long career for Sheridan in the West. Sheridan quickly went to work by planning a winter campaign to respond in force to violent acts committed by natives in the region. As such, Sheridan believed that his soldiers would be unable to chase the horses of the Indians during the summer months, so he used them as a defensive force the remainder of September and October. His forces were better fed and clothed than the Indians and they could launch a more efficient campaign in the winter months where the Natives settled into winter quarters. His winter campaign of 1868 started with the 19th Kansas Volunteers and Custer's 7th Cavalry, along with five battalions of infantry under Major John H. Page setting out from Fort Dodge on November 5. Sheridan directed the opening month of the campaign from Camp Supply. A few days later, a force moved from Fort Bascom to Fort Cobb consisting of units of the 5th Cavalry Regiment and two companies of infantry, where they met up with units from the 3rd Cavalry leaving from Fort Lyon.

The Units from the 5th and 3rd Cavalry met at Fort Cobb without any sign of the 19th Kansas, but they had a lead on a band of Indians nearby and Custer led a force of the 7th Cavalry after them. Custer's force attacked the Cheyenne Indians and Black Kettle in the Battle of Washita River, and an estimated 100 Indians were killed and 50 taken prisoner. A unit went missing under Major Elliott's command. Immediately following the battle, Sheridan received backlash from Washington politicians who defended Black Kettle as a peace-loving Indian. Following Washita, Sheridan oversaw the refitting of the 19th Kansas and personally led them down the Washita River and continued toward the Wichita Mountains. He met with Custer along the Washita River and they searched for Major Elliott's missing unit. They found the bodies of the missing unit and the bodies of Mrs. Blynn and her child who had been taken by Indians the previous summer near Fort Lyon (Hutton, Phil Sheridan and His Army, 28-114).

The defeat at Washita had scared many of the tribes and Sheridan was able to round up the majority of the Kiowa and Comanche people at Fort Cobb in December and get them to reservations. He began negotiations with Chief Little Robe of the Cheyennes and with Yellow Bear about living on the reservations. In 1869 during negotiations with Comanche Chief Tosawi reputedly told Sheridan, "Tosawi, good Indian," to which Sheridan supposedly replied, "The only good Indians I ever saw were dead." These words were later recounted by an officer present and are discussed in Dee Brown’s Burry My Heart at Wounded Knee . These words were taken out of context and changed to become the quote “the only good Indian is a dead Indian” which would be attached to Sheridan forever.

Following the success of his winter campaign and the election of President Grant, Sheridan received a promotion. On March 4th of 1869 Major General Philip Sheridan was promoted to Lieutenant General of the United States Army, the second highest ranking officer in the Army now behind General of the Army William T. Sherman. Sheridan assumed command of the Military Division of the Missouri and was responsible for four departments: the Department of the Missouri (Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, and the Indian Territory); the Department of the Platte (Iowa, Nebraska, and portions of the Wyoming, Utah, and Idaho territories), and the Department of Dakota (Minnesota and the Territories of Montana and Dakota) and in 1870 the Department of Texas (Texas and the Indian Territory). This made Sheridan commander of almost the entire West. He was in command of military campaigns against the Natives and responsible for controlling any threats posed by them against the people of the United States. This made Sheridan the most influential man in the West (Hutton, Phil Sheridan and His Army, 115).

Who says Sheridan is important?

Philip Sheridan has been the target of numerous biographies and analysis from a variety of Civil War and Western historians. The Timeline has a thread for the life of Phil Sheridan and how his story and life fits into the larger picture of the American West and the U.S. Cavalry. Sheridan was influential in the developement of the Union Cavalry in the last years of the Civil War and their use in the West after the war. As a high ranking officer in the Army, Sheridan led thousands of men and consistently deployed cavalry in the field to combat the natives. This began in 1868 in his Winter campaign, the decision for which was influenced by his experience in the West as a young officer and in the cavalry during the Civil War. There are multiple instances in which Sheridan requests more cavalry be sent to the West. While Sheridan's story provides evidence and examples of how he was influential in the West and in cavalry history, evidence has not yet been presented in this project to show Sheridan's importance at this time amongst the people and his fellow officers. To see how the public viewed Sheridan and their knowledge of him, newspapers from the time are a great reference to infer this. The importance and influence of newspapers and historical examinations of them are discussed in more detail in the Public page. The newspapers of the nineteenth century carried influence in the public and directly impacted public opinion. As such the articles in the paper are arguably reflective of how the public percieved particular topics, like Phil Sheridan. Furthermore, military publications like the Army & Navy Journal were written for and by officers in the military at this time. Their articles and how Sheridan was discussed in them is reflective of how officers at this time viewed the general. The graphs below will further illistrate the importance of Phil Sheridan during this time by looking at the newspaper and journal search results. If any of the visuals below do not load, please click on the visual's title to open a PDF file of the image, or go to the Sources page where all the visuals for this project are listed on the left hand side of your screen. Please take note that images of the Voyant tools are not interactive like the imbeded web tools.

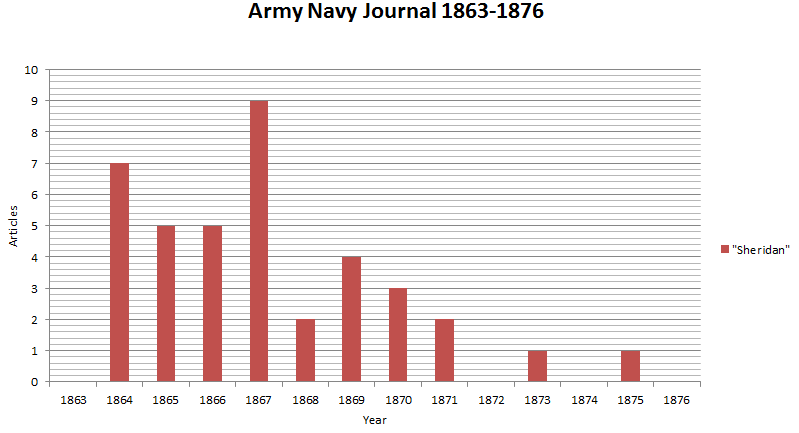

Figure 4: Sheridan in the Army Navy Journal 1863-1876

The Army & Navy Journal (ANJ) will be discussed in more detail in following portions of this project, but for further understanding of Figure 4: the Army Navy Journal was a military publication that was written, edited, and primarily read by military officers and veterans of the U.S. Army. That being said figure 4 shows the number of times "Sheridan" appears in articles published between 1863 and 1876. Following the war there were articles being written about him and they peaked in 1867 with 9 and then dropped off until his winter Campaign where they spiked again. While there are periods where Sheridan is not discussed frequently in the ANJ, it is intersting to see the trend in these articles. As Sheridan was rising through the ranks and eventually recieved the rank of Lt.General in 1869, there were more and more articles being written about him or referencing him. Once he obtain this high rank and was in control of the majority of the West these articles referencing him written by fellow officers and veterans becan to decline dramaticially. This raises many interesting questions. Was this because of Sheridan in some way or did the trend in ANJ topics simply shift? These questions are not answered in this analysis, however this does show the importance of Sheridan during his rise to power in officers discussions.

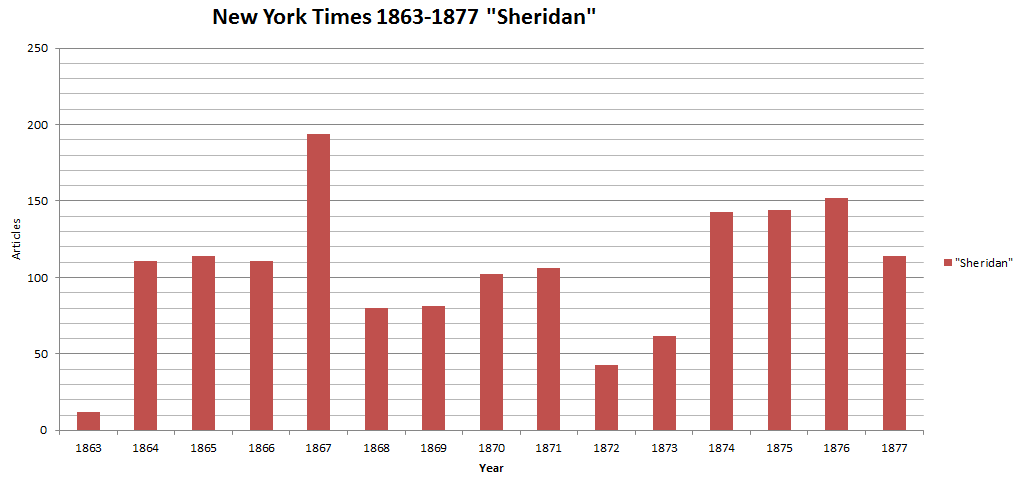

Figure 5: Sheridan in New York Times publications 1863-1877

Figure 5 above shows the articles published in the New York Times between 1863 and 1877 that contained the word "Sheridan" in them. From 1863 to 1877 there was an average of 104 articles written in the New York Times per year that referenced Phil Sheridan. While this coverage varied over time, with highs in 1867 and 1874 as well as lows in 1863 and 1872, over this fifteen year period Sheridan appeared in a New York Times article once every three and a half days. From this amount of coverage it is clear that he was a known figure to the public and clearly influential in the West. More detail on how Sheridan is portrayed in these articles is shown in later sections of this project.

These graphs do not attempt to present any evidence on the way that Sheridan was presented in these publications or how he was percieved by the officers and the public. This data is simply presented in order to argue that Sheridan was being actively discussed and reported on at this time. While these articles may be positive or negative illistrations of Sheridan, it is clear that he had established himself as a prominent figure in American news and in officer's discussions. As the most important American cavalryman after the Civil War and his high position in the military, Sheridan directly influenced not only the American West and native Americans but also the history of the U.S. Army and Cavalry. As such he is a crucial part of this examination and these histories and should be included in this conversation.